Table of Contents

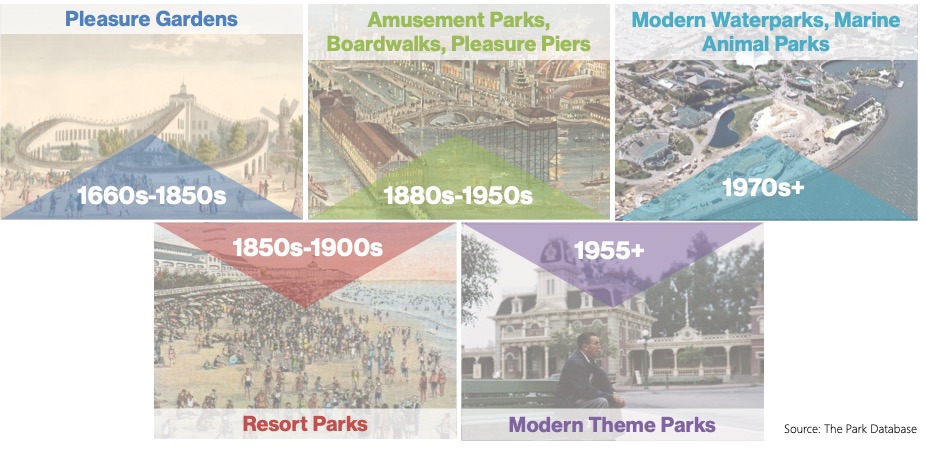

Toggle“Location-based” entertainment for the masses has been around a long time; Ancient Rome is remembered for their games of gladiatorial combat and sporting events in the Colosseum, the Mayans played a ballgame called pitz in large stadiums, and medieval Europe regularly hosted carnivals and fairs centered around religious holidays and markets.

All of these forms of entertainment deserve their own post, but in this study, we’ve traced the concept of modern theme parks as far as we could go – and like many origin stories, it begins in a garden.

The oldest extant theme parks in our database are three attractions in Europe, opened between the 16th and 19th centuries. A summary of their early history:

- Bakken, in 1563, originated as a series of carnival entertainments built around hot springs, evolving from a private hunting ground, into an animal park, then further into public park grounds during the 18th century.

- The Wurstelprater similarly went through an evolution from royal hunting grounds into a public park in 1766.

- Tivoli Gardens was also conceived by royal charter in 1843, when then-king Christian VIII granted a concession for the pleasure grounds to private entrepreneur George Carstensen.

A theme park can’t exist without acres and acres of land, and the word itself (theme “park”) contains a hint of what these attractions originally were: large, green spaces within urban environments, set aside by royal charter, for the enjoyment of the people.

I.e., parks.

And in Europe during the 17th to 19th centuries, this kind of public pleasure ground, or pleasure garden, reached the heights of development.

Pleasure Gardens

So what were these mysterious pleasure gardens?

Now largely forgotten, these were the theme parks of their time. Pleasure gardens were one of the chief sources of urban entertainment in both Europe and the United States during the 18th and 19th centuries.

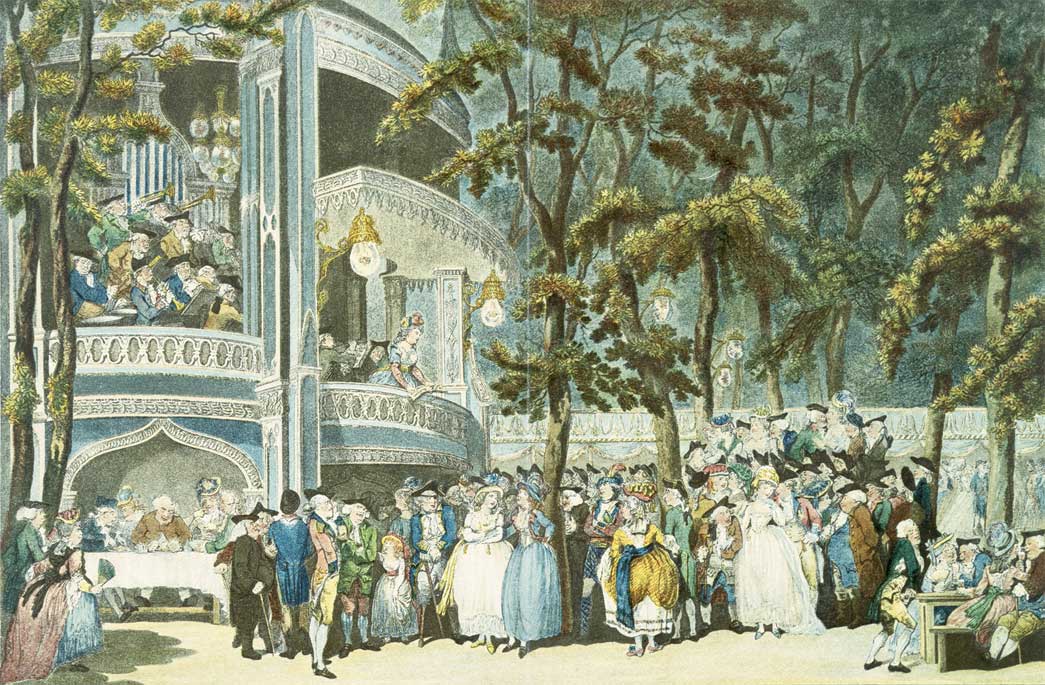

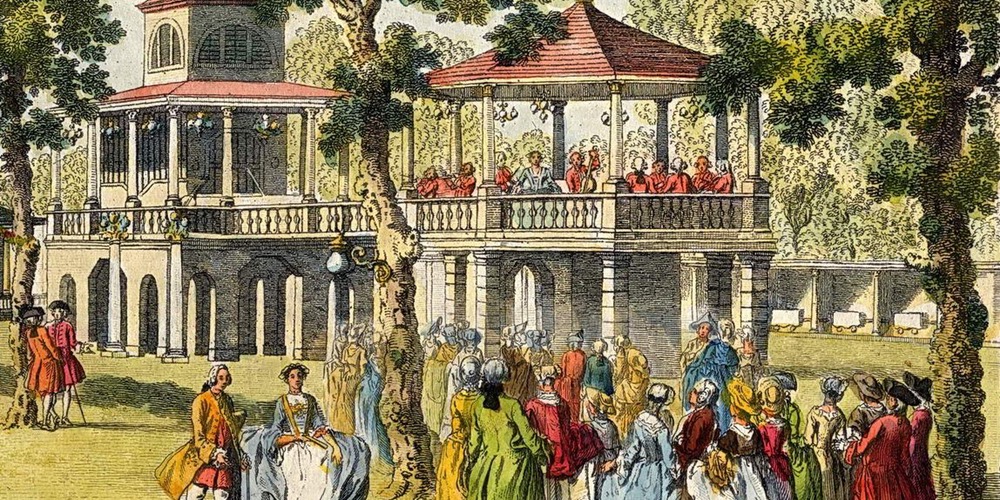

With lushly landscaped grounds, they contained palatial architecture, Chinese pavilions and French promenades, covered dining booths, floating balloons, bowling greens, and a variety of al fresco musical entertainment under the stars. They were early nightclubs and amusement parks all in one.

They included features like:

Circular walks: at both Vauxhall Gardens and Ranelagh, strolls were curiously regimented in a circular direction to the tune of music. Ranelagh in particular was noteworthy for having the largest rotunda of them all, under which visitors strolled as if around an axis. When a bell rang, the promenaders all turned around and started walking in the other direction.

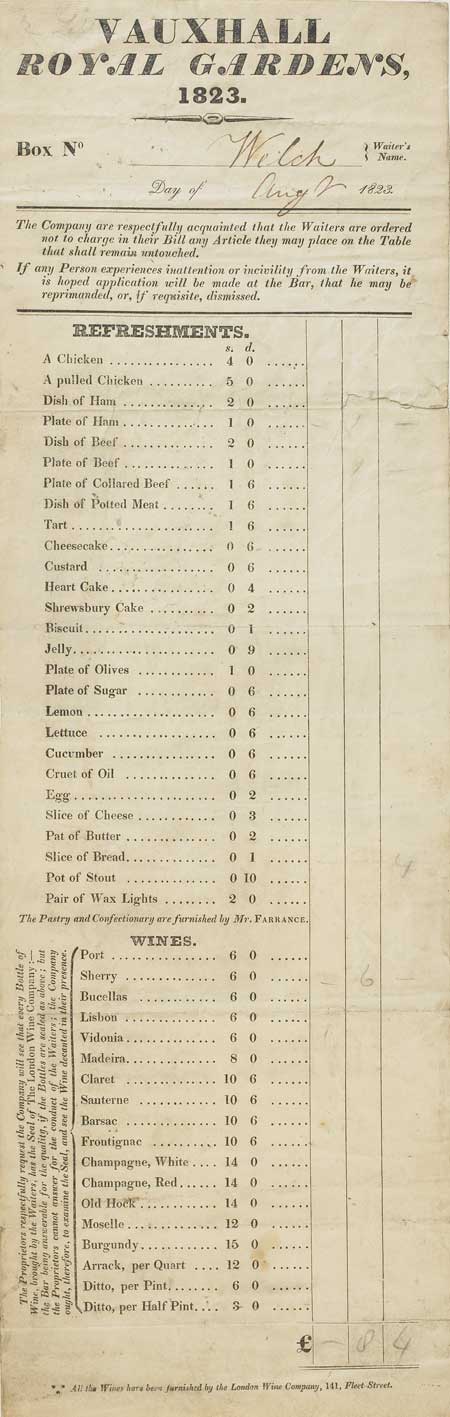

Gate fee: access to these pleasure gardens was ticketed, with the same kind of ticket schemes later to be found in their descendants, with annual and lifetime passes available. The concept of ticketed admission, however, was so offensive to some, that full-scale riots and fights sometimes came about between those who paid and those who didn’t.

Restaurants: meals were a common feature; the Spring Gardens at Bath actually hosted brunch on Monday and Thursday mornings, after which music and dancing were in order. Such early-morning festivities were then followed, around noon, by two hours of walking. Supper boxes were located along the main walks and public areas to allow patrons dinner and a show.

Striking landscapes: of course, these gardens had…gardens. Richly landscaped features, mazes, from bowling greens and lawns, to extensive flower gardens, and avenues of trees, were the centerpiece of these developments. Striking architectural features entertained visitors at Ranelagh, from the Chinese Pavilion and Fountain of Mirrors, and guests commented favorably on the bucolic scenes, interspersed with lambs, at the Rural Downs in Vauxhall.

Music: music-accompanied entertainment ranging from operas, open-air masquerades, and dancing, were standard fare. Ranelagh Gardens once hosted a 9-year Mozart, and Vauxhall held an annual reenactment of the Battle of Waterloo, with 1,000 soldiers.

Vauxhall even featured early music “speakers”; musicians were hidden in the shrubbery or on platforms in the trees, evoking a soundtrack to certain ‘lands’, or different areas of the park.

Evening fare: most major gardens hosted concerts in the evening, many often running until 11pm, and masquerades. They functioned almost as nightclubs in this regard, with strollers in the more fashionable gardens (e.g. Ranelagh) not appearing before midnight and 1am, and music playing at the Marylebone until 3am. To accommodate such late-night festivities, gardens were extraordinarily illuminated; Vauxhall was said to use up to 14,000 lamps in its lighting.

Rides: balloon ascents became popular in the early 19th century, and gardens in France were first to adopt thrill rides, in the form of Russes Montagnes (Russian Mountains), early predecessors to roller coasters, with carriages that wheeled at high speeds down a track. Introduced in 1817, the Aerial Walk at the Baujon Gardens was especially notable for its dual track system, featuring cars that sped downwards at 40 miles an hour, and had to be pushed by attendants back up.

In summary, we can draw a clear lineage from these early pleasure grounds to modern theme parks. Theme parks like Bakken, Prater, and Tivoli Gardens clearly embody this evolution.

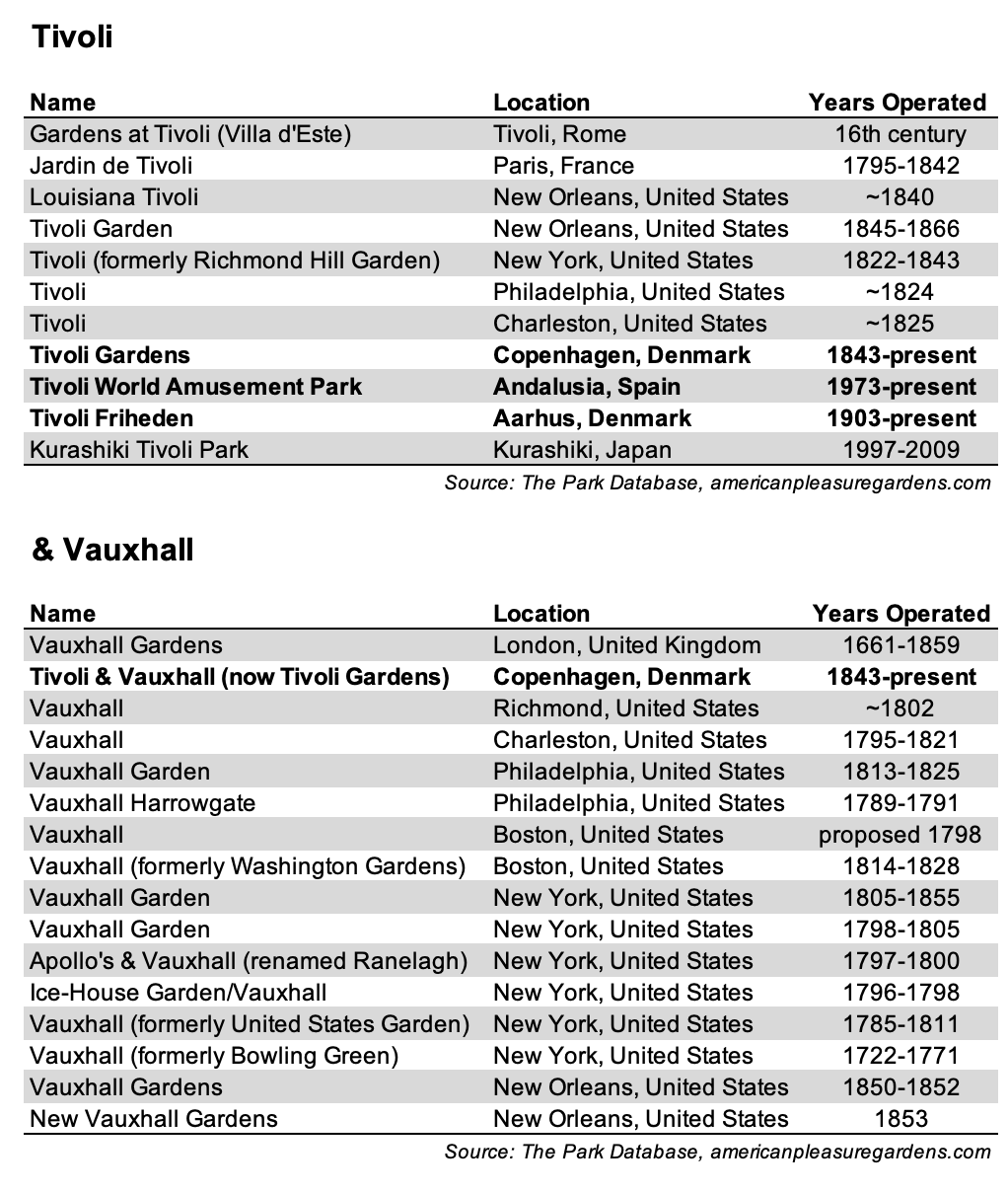

In fact, Tivoli Gardens’ original name contains further evidence of this history. When it opened in 1843, Tivoli arrived at the tail end of this pleasure garden period, and its very name was a reference to the foremost gardens prevalent at the time: the park was originally known as Tivoli & Vauxhall.

“Tivoli” alluded to one of the most famous pleasure gardens of Paris (Jardin du Tivoli), and the latter referenced Vauxhall Gardens, the foremost pleasure garden in London. This was a branding decision that we imagine today would be akin to naming a theme park ‘Disney & Universal’.

Both Tivoli and Vauxhall were popular names, and had multiple locations throughout the United States and Europe.

End of an Era

Pleasure gardens began to fade from prominence during the beginning to mid-19th century. This is a sort of lost period when pleasure gardens start to close, but without clear-cut causes.

Preceded by the closure of the notable Ranelagh Gardens in 1803, Jardin de Tivoli in France closed in 1842, and London’s Vauxhall Gardens, the granddaddy of them all, closed in 1859. This coincided with a similar period in the United States; every American Vauxhall closed its doors between the early 1800s to the 1850s.

Was this because of changes in consumer sentiment? Worsening economic conditions? Urban redevelopment? Emerging new forms of entertainment? It’s not clear.

Why these gardens closed on both sides of the Atlantic is a mystery, but the phenomenon might partially explain why pleasure gardens in general have been forgotten: with such a gap in the historical record, it appears as if the rise of theme parks comes out of nowhere, a clean break from the past.

Resort Parks, Picnic Groves, and Trolley Parks

New forms of amusement arose in the mid-1800s. The Age of Industrialization was also the age of railroads, allowing a new class of consumers with newly earned leisure time to travel far and wide in search of amusement.

Parks and gardens in urban areas were less appealing to this new class of guests than waterfronts, picnic areas, and resorts out in the country.

It was the era when people started “going to the beach,” seeking waterfront resort areas and country air, and steamship routes and trolley lines shuttled guests out to these areas. In fact, many of these developments were purposely created by streetcar companies at the terminus of their lines in order to drive usage during the weekends (trolley parks).

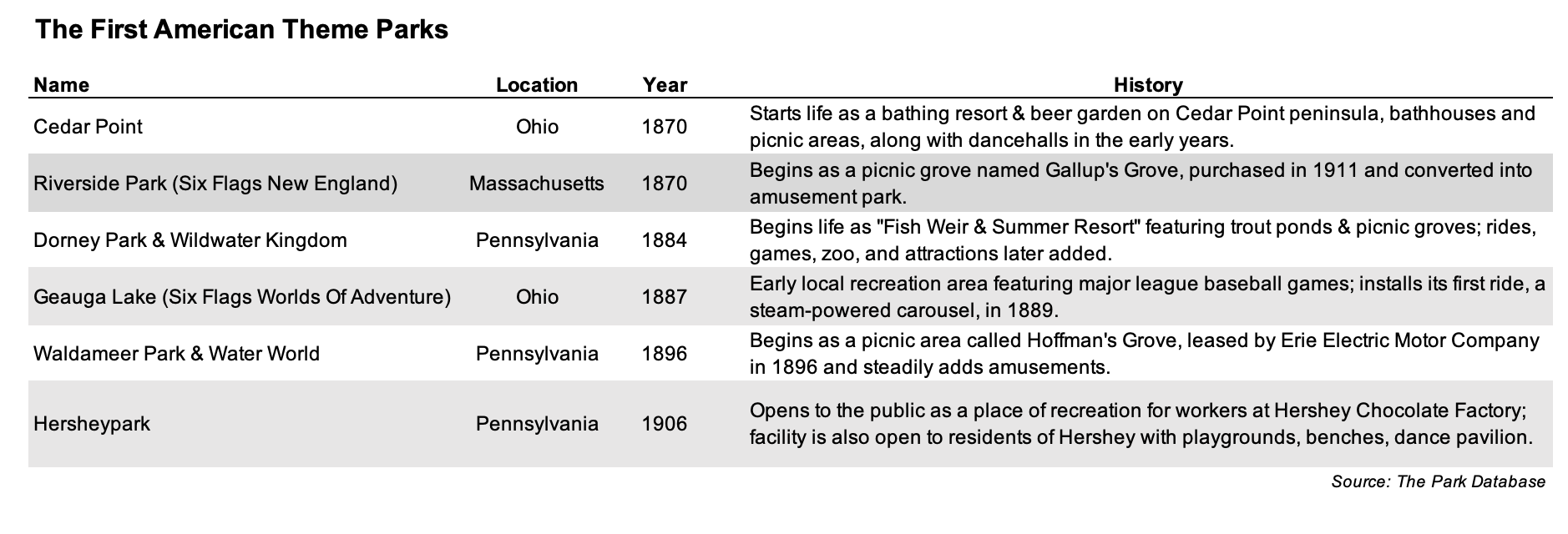

It’s no coincidence that the United States’ oldest existing theme parks had their genesis during this period (the 1870s to the 1890s), originating as sprawling picnic and waterfront resort grounds.

- Cedar Point began life in 1870 as a bathing resort and beer garden, with dancehalls and hotels. Steamboats provided service to the peninsula.

- Dorney Park & Wildwater Kingdom, in 1860, started as a fish hatchery with trout ponds and shady picnic groves, with refreshment stands, hotel, restaurants, and rides added over time. It was named Dorney’s Trout Ponds & Summer Resort in 1884.

- Riverside Park (later Six Flags New England) began as a picnic grove in 1870.

- Geauga Lake (later Six Flags Worlds of Adventure) installed its first ride in 1889, previously it had been a lakefront recreation area hosting major league baseball games.

- Waldameer Park & Water World began life in 1896 when it was leased by an electric car (trolley) company; previously it had been a picnic area.

What’s notable is that the early forms of amusement in these “resort parks” (for lack of a better term) very much resembled the earlier pleasure gardens that they replaced: picnicking areas within forests or by the water featured prominently, while dancehalls and refreshments were usually among the first attractions added.

Amusement Parks

The nature of amusement began to evolve with the industrial age, when mechanized amusements appeared. Carousels were invented in the 1860s, electric roller coasters arrived in the 1880s, and the first Ferris wheel debuted during the World’s Columbian Exposition (world’s fair) held in Chicago in 1893.

These forever changed the guest experience, and heralded the beginning of the amusement park era. The first coaster opened at Cedar Point in 1892, while Geauga Lake’s first ride, a steam-powered carousel, was added in 1889. Waldameer added its first coaster in 1907.

It was the dawn of a new age, and pleasure piers, boardwalks, and amusement parks had their moment.

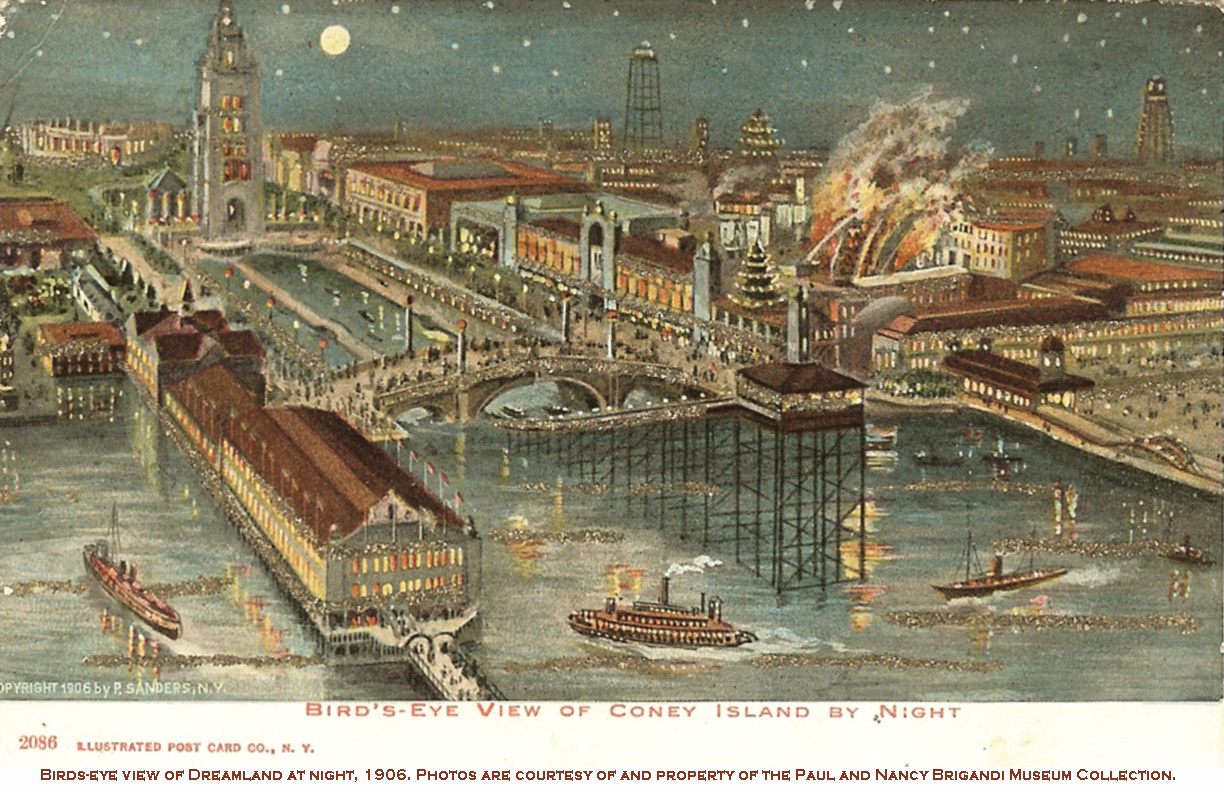

The traveling circus, started by PT Barnum in 1871, peaked during this period. Coney Island-style boardwalks emerged, and with them, the first amusement parks as we know them: Coney Island’s three theme parks (Steeplechase, Luna, Dreamland) opened between 1897 and 1904, while Britain’s first amusement park, Blackpool, opened in 1896, and was being referred to as an “American amusement park” by 1903.

In Europe, Manchester’s Royal Botanical Gardens (opened 1829) announced a reopening in 1907 as the White City Amusement Park, complete with gondolas, coasters, and a giant water chute. Vienna’s Prater added a carousel in 1887, and a ferris wheel followed ten years later. Meanwhile, Tivoli Gardens (Copenhagen) continued its ongoing evolution with the addition of a roller coaster in 1914.

![Rutschebanan, Tivoli Gardens] - Nordicember pic #24 : r/rollercoasters](https://external-preview.redd.it/kClTfWSLg9L1PRV6AAqw97UAqNwZk8n13Ph1SZyT5-s.jpg?width=640&crop=smart&auto=webp&s=b3f688410ae793ef86a114e75c33e0229d01bd35)

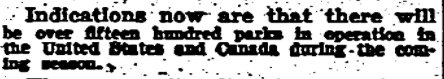

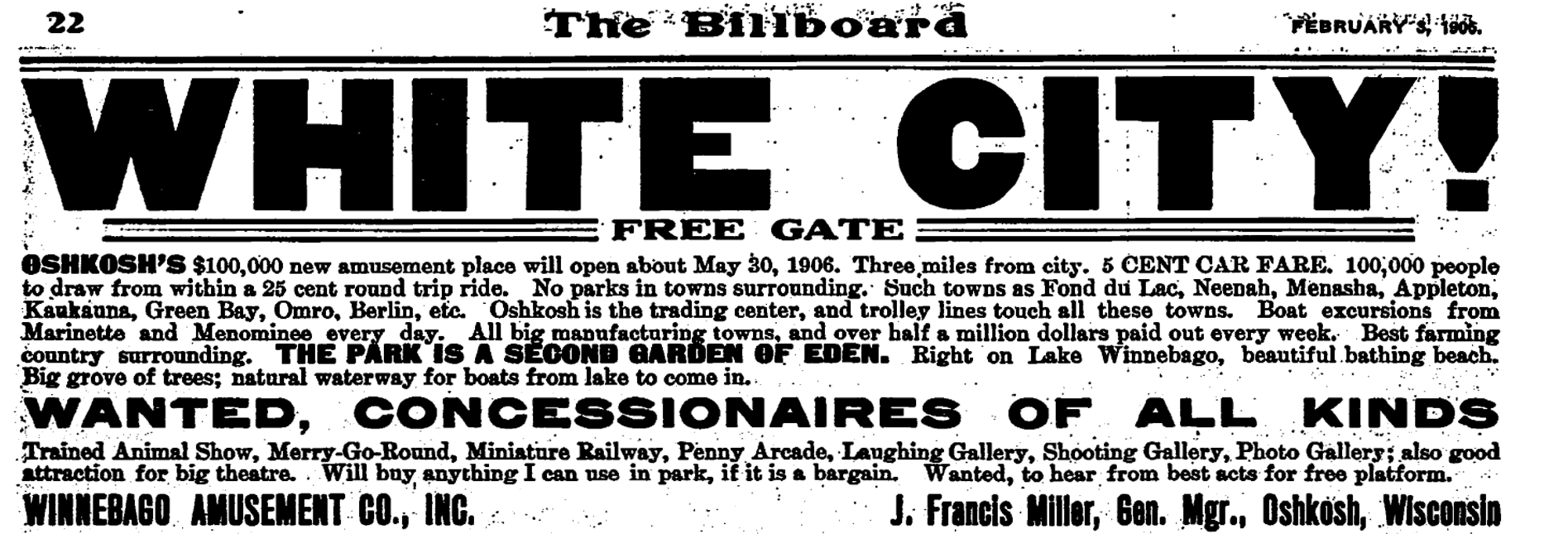

Competition was rampant. In the United States at the dawn of the 20th century, over 1,500 pleasure piers, resorts, traveling carnivals, and summer amusement parks featuring rides, picnic grounds, concession stands, amphitheaters, musical pavilions, and show extravaganzas were planned every season.

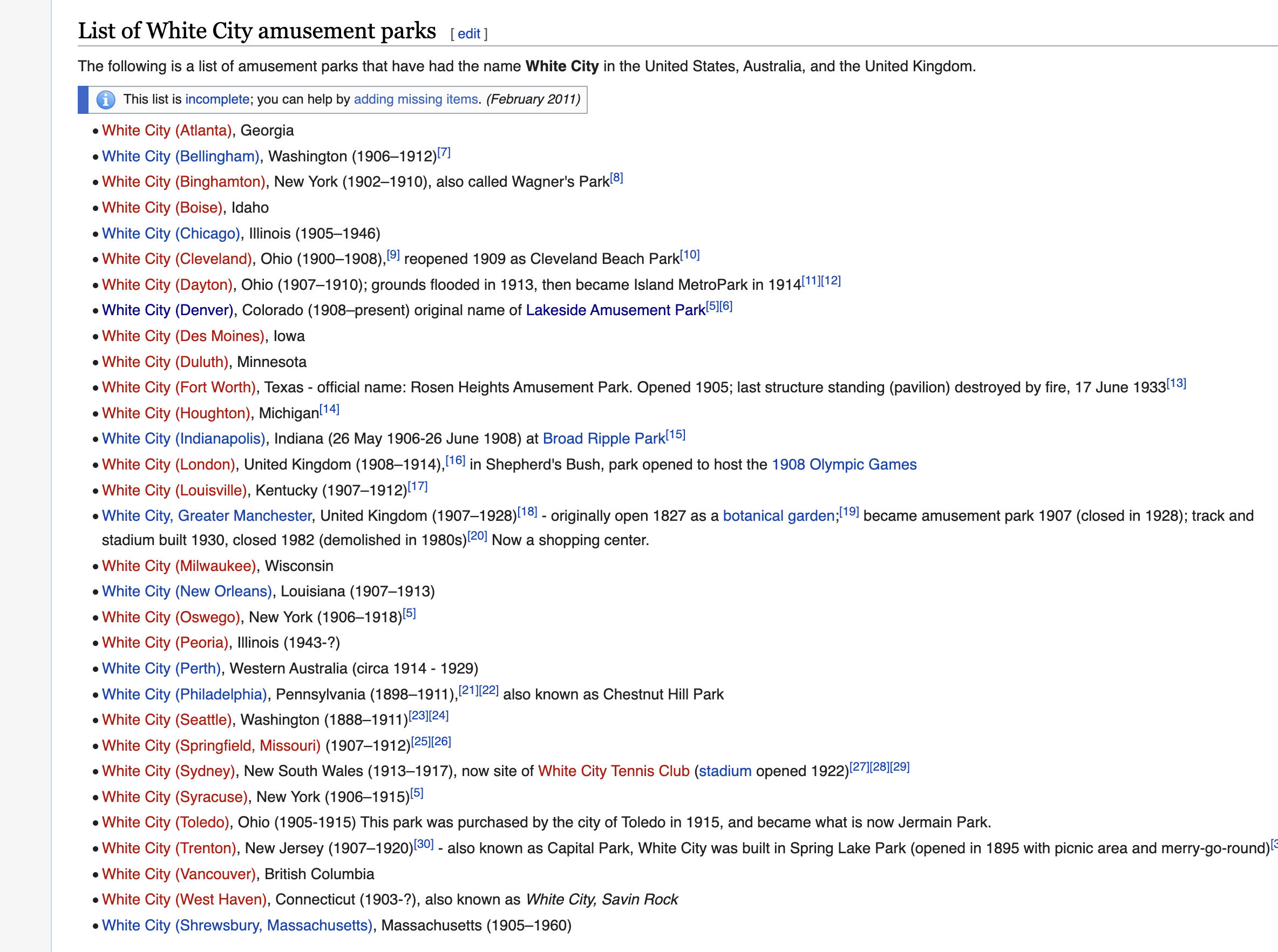

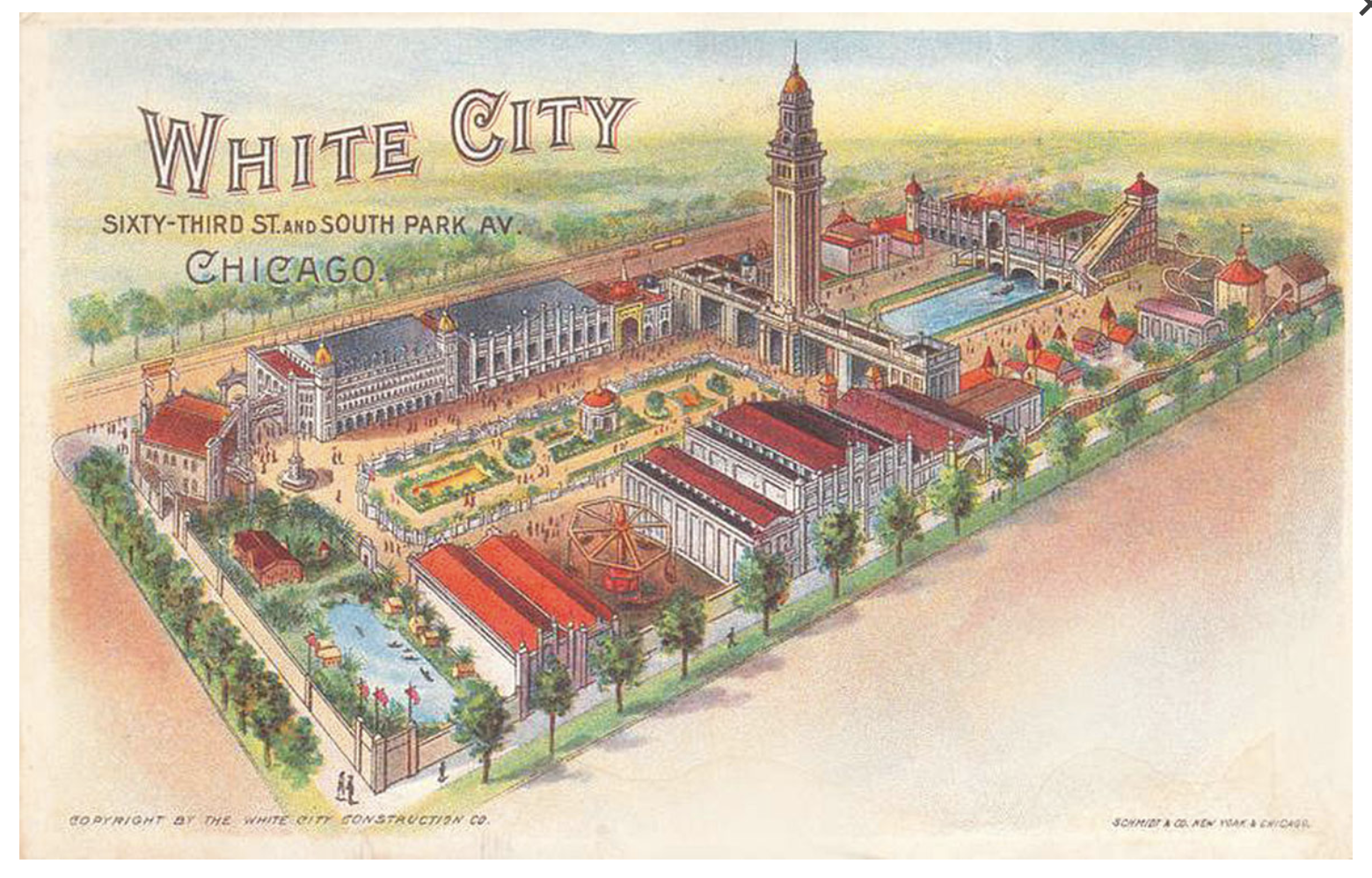

Much like Vauxhall or Tivoli had been to pleasure gardens a century earlier, the term White City became synonymous with amusement parks, with an attraction mix largely consisting of a shoot-the-chutes, coaster, and midway. White City had been a section of the Chicago’s world fair in 1893, and over the next two decades, lent its name to dozens of amusement parks in the United States, Australia, and United Kingdom.

Modern Theme Parks

Without exaggeration, after two world wars in the 20th century, the world was forever changed.

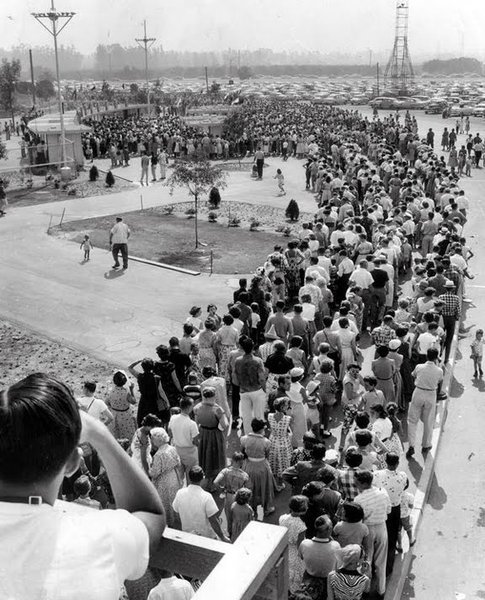

And in many ways, Disneyland’s opening in 1955 signified a break from what had come before. Disneyland wasn’t the first theme park, but it was the first of its kind, a rejection of the prevailing type of amusement park of the time.

Walt Disney had railed against the anarchic nature of existing amusement parks, which he felt were characterized by unfair games, pickpockets, and operated by rough “carnies” who were little more than rip-off artists. The aggregate experience was an unwholesome, chaotic whole.

In contrast, Disneyland would be a master-planned, pristine, and controlled environment. Unlike at boardwalks and pleasure piers (e.g. Coney Island), admission into Disneyland wouldn’t be free, therefore keeping out rabble-rousers and drunks.

This concept was so revolutionary that no one believed it would work.

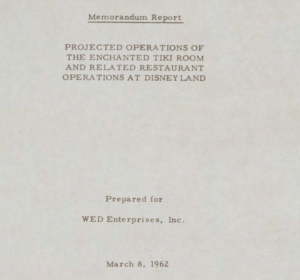

In 1953, Walt Disney’s feasibility consultant, Buzz Price, cornered four then-kings of the amusement park industry in a hotel suite, and plying them with liquor and cigarettes, conducted what today would be called a focus group for Disneyland.

So crazy did Disneyland seem at the time, that the men – William Schmidt, owner of Riverview Park in Chicago, Harry Batt of Pontchartrain Beach in New Orleans, Ed Schott of Coney Island (Cincinnati), George Whitney of Playland at the Beach in San Francisco – unanimously declared the concept would be an abject failure.

Among the negative comments (there were no positive ones), quoted liberally from Disney’s Land by Richard Snow:

- “All the proven moneymakers are conspicuously missing, no roller coasters, no Ferris wheel, no shoot-the-shoots [sic]…no carny games like the baseball throw”;

- “Without barkers along the midway to sell the sideshows, the marks won’t pay to go in”;

- Not “enough ride capacity to make a profit”;

- “Custom rides will never work…besides, the public doesn’t know the difference or care”;

- “Things like the Castle and Pirate Ship are cute but they aren’t rides so there is no economic reason to build them”;

- Main Street “is loaded with things that don’t produce revenue”;

- The single entrance gate “will create another terrible bottleneck. Entrances should be on all sides for closer parking and easier access.”

- The Jungle Cruise “will never work because the animals will be sleeping and not visible most of the time”;

- “Walt’s screwy ideas about cleanliness and great landscape maintenance are economic suicide. He will lose his shirt by over spending on things the customers never really notices”;

- “Tell your boss [Disney] to save his money. Tell him to stick to what he knows and leave the amusement business to people who know it.”

As it turned out, Disney might have known something they didn’t know about consumer psychology and creating magic.

Today, the other operations are closed: Pontchartrain Beach shuttered in 1983, Playland San Francisco in 1972, Riverview Park in 1967. Coney Island Cincinnati sold all of its attractions to neighboring Kings Island in 1971 and reopened in 1973 as a waterpark.

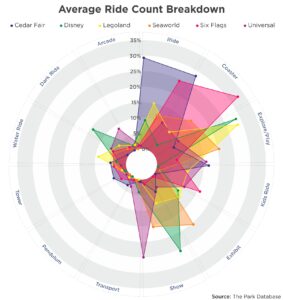

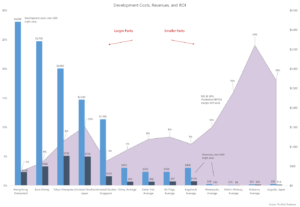

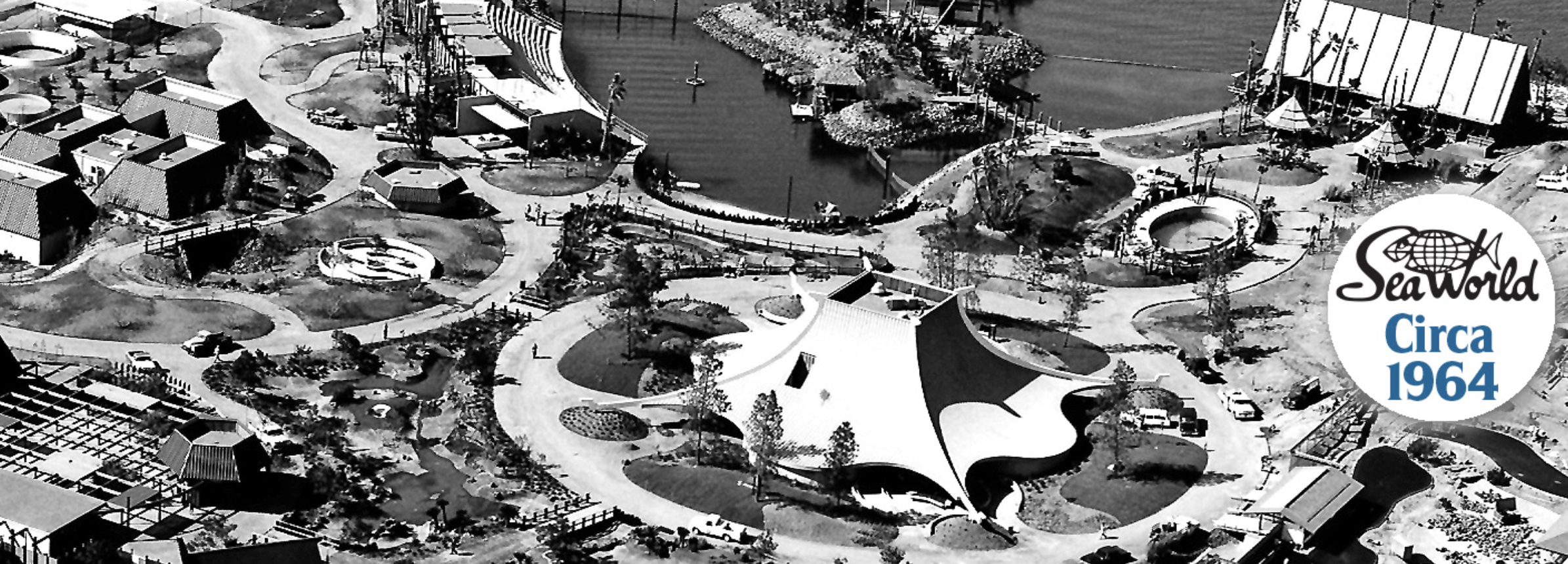

Disneyland was the beginning of a Cambrian explosion in themed entertainment. Universal Studios converted itself from a lone tour to a full-fledged theme park beginning in the 1960s, a decade that saw the opening of the first Seaworld and Six Flags parks.

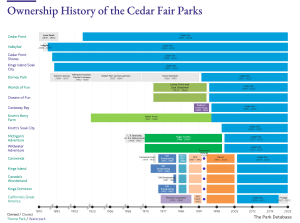

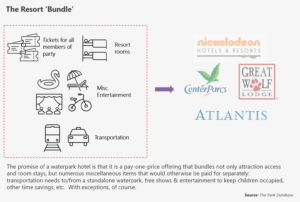

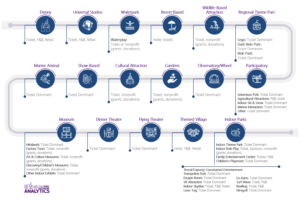

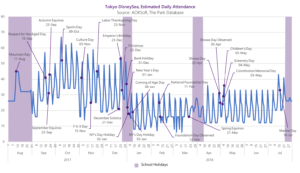

With the opening of Disney World in the 1970s, theme park resorts took on their modern form. Over the decades, theme parks expanded by type (see detail here), but also globally, with Japan becoming a notable adopter of the modern concept.

When we look back at this long arc of theme park history, it’s very difficult for us to ever agree with statements saying that theme parks “are dead” or “dying”. The need for communal recreation seems baked into human nature. Although its various forms might change over the centuries, parks are here to stay.

– Brought to you by the Park Database.

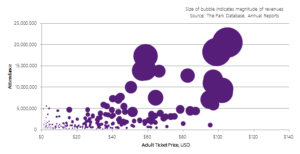

Theme parks worldwide attract hundreds of millions of visitors annually, and today are one of the dominant forms of location-based entertainment. Find out more about them here.

Other sources:

The Pleasure Garden, from Vauxhall to Coney Island, edited by Jonathan Conlin

Disney’s Land: Walt Disney and the Invention of the Amusement Park That Changed the World, by Richard Snow