Table of Contents

ToggleWon here. This is my interview with Ray Braun, partner emeritus at Entertainment & Culture Advisors, and former lead partner of the Attractions Practice at Economics Research Associates. Over a 50-year career, Ray has truly worked with everyone. Here, we cover a wide range of topics and developments, including his work with the Getty, Universal Studios, Malaysia’s sovereign wealth fund, Elitch Gardens, Sony, Legoland, and more.

Enjoy my conversation with Ray.

ERA

Won: We worked together, but I don’t think I properly heard the story of how you joined ERA and what that was like in the seventies. In my mind that seemed to be the glory period of theme parks, at least in the US. That’s when Disney was building Disney World, and theme parks were just starting to open around the world as well. You were there from the beginning, so I’d love to hear about how you came to join ERA and what that was like, and what the general period was like?

Ray Braun: So, truth be told, I wasn’t really there for the very beginning. The very beginning was launched by Walt Disney and this amazing guy named Harrison Buzz Price. Walt invited Buzz to help him figure out how to do it and where to build Disneyland.

Then Walt said, you’re pretty good at this. Why don’t you start your own company? Because (Buzz) had been at Stanford Research Institute at the very outset when they found the site in Anaheim. And he started ERA (Economics Research Associates) and that grew. Disneyland opened in ’55, Buzz started ERA in ’58 or something like that.

And he eventually brought some other partners in. ERA grew into an extensive land-use economics firm – a consulting firm.

I actually joined in ’71 because I thought I wanted to be a real estate developer. After a while working on various real estate projects, I saw that the guys at the other end of the shop were working on entertainment projects and having more fun. So I thought I should get involved in that. That led to me be very involved in that and eventually become the head of the practice as Buzz moved on to other pursuits.

So, that’s how it started; I became head of the entertainment practice for 25 years, for the whole firm. We were dominant in the field of entertainment, real estate development projects.

Won: Right.

Ray Braun: And literally just about everybody, you and I included, sort of came from that wellspring of the early days of ERA. I mean, all of the competitors out there.

Won: Sure.

Ray Braun: After a while, we’ll talk about some projects and stuff that we’ve done in the interim. But after a while, we ended up selling ERA, to AECOM. That was in 2007.

2010, several of us; myself, Matt Earnest, Christian Aaen, and Ed Shaw decided to leave the AECOM version of ERA and start a different company, ECA, trading shamelessly on the name, the brand of ERA.

We wanted to have a practice focus on continuing the practice that we had with the clients. ERA did several other things with real estate and resort development and city redevelopment projects, things like that. We just wanted to have a specific focus on entertainment development economics.

Entertainment. And we’ll talk about that maybe a little later. The culture part.

Won: Understood. Thanks for the overview.

Ray Braun: A quick recap of 50 some years.

Won: When you first joined, were you working on Disney World? Because that’s when that was all going on, back in the seventies.

Ray Braun: No. I joined in ’71 and the Disney World planning stuff was started in the mid-sixties, the vision of 27,000 acres and all that.

One of my colleagues, you’ll remember Austin Anderson, his very first job at ERA, as he tells the story, his very first job was the economic impact of Disney World on the state of Florida. And so he walked right into it.

Elitch Gardens

Won: So what were some of your first projects in the entertainment practice?

Ray Braun: Well, some of the very first ones weren’t that notable, but I’ll talk about some early projects to give you a sense.

I worked with Elitch Gardens in Denver. I was working on something else in Denver, a fairgrounds project in Adams County, north of Denver.

And we were looking at different options of what to do with that property. And one of the ideas was maybe some kind of theme park. Well, in those days, there were two amusement parks in Denver. One was Elitch Gardens, it was on the fourth generation of family ownership – the Gurtler family.

And as part of my project of working for this government agency, north of Denver, I went and called on the Gurtlers and said, one great idea we have is to look at doing a theme park up here. You’re the established classic theme amusement park in Denver. But you’re very much hemmed in by… I forget how many acres it had, but it wasn’t very much. But it had the classic rollercoaster and a great history. So, I started talking to them and they said, no, no, no, we’re fine.

But then after a couple years, they called me back and said, we talked about this thing. So, maybe we ought to look at that. So for years, we looked at where the best site would be. And I was a part of that process. We were very close to going to a location south of Denver.

But we settled on this incredible property right in the middle part of Denver, right along the river, rail yards that had a lot of contamination issues and stuff. They worked out a very complicated land deal, and were able to get a park adjacent to downtown Denver. So that was really interesting. That all took place over the 10 or 15 years of working with them, a long duration to be realized. Eventually, it got sold to Six Flags. And that was that.

Won: Do you remember how that land acquisition process worked? It being so close to downtown Denver, I imagine that would’ve run into a lot of challenges.

Ray Braun: Well, because it was a rail yard. The big switching yard in Denver; Burlington Northern and other railroads, Santa Fe. And it was a great asset with Denver being so close. So they were very involved. And he ended up building the stadium there in an arena and the amusement park. It was complicated; there was a lot of contamination. And the city had to sort of indemnify the cleanup of the process and was fortunate it worked out as well as it did.

But I thought it was an absolutely awesome site. And the idea of doing that, it wasn’t really quite a full theme park, but a big amusement park in the middle of a city. So it’s a little Tivoli Gardens-ish.

Won: In general, what were those early days in terms of how different it is from now? Could you paint a picture of what the 1970s and early 1980s were like; Disney was just opening Disney World and Universal was just getting started, and even the regional parks were just getting started, I think.

Ray Braun: It was a sort of a rush of activity. We recognized it as such then, but certainly the Disney set the stage with Disneyland.

And I like to say, Walt Disney taught us everything we need to know about theme parks. First of all, number one, he invented theme parks with Disneyland. Number two, he built Disney World and taught us that building a destination is better than building a park.

And the idea of selling several days instead of several hours is much higher revenue potential. But that concept was ahead of its time, of building the complete destination. Hadn’t caught on in any way yet.

The big story of the 70s and 80s was building regional parks and all of the markets big enough in the United States. And some elsewhere.

So you had the rise of Six Flags, pardon me – Six Flags really only built three parks. They built Texas and then Atlanta, and then MidAmerica, and then they acquired everything else.

So there they became a chain of regional parks. There were a lot of other independent parks that were built. There was Opryland and several others, but the King’s Group that was actually Taft Broadcasting built the first park, their first park in Cincinnati. And then they built King’s Dominion.

And eventually that got rolled up with several other parks, Carowinds and some others into what was called King’s Entertainment, which became Paramount Parks.

And then got rolled into some other parks into Cedar Fair Group. But all that consolidation came later.

The real thrust was entrepreneurial people or organizations building a park to service their region, their area, the old 50- and 100-mile radius.

Rise of China

Won: When did you first start seeing activity from international clients?

Ray Braun: Well, Buzz had done a number of things with some old line European guys. And some of that carried over, you know the Macks, Europa-Park and Efteling and some of those. So it was kind of a European story.

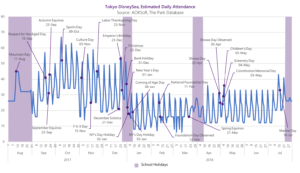

Then eventually, there seemed to be a little bit of action in Asia. And of course, Disney again led the way with Tokyo Disneyland. I’m trying to remember the exact sequence in years… did several things in Japan. I started in the eighties doing things in Japan.

Japan was having a real surge, remember the whole trophy property stuff?

Won: Yeah.

Ray Braun: Buying everything. And they wanted to build theme parks in Japan. And then a real notable time came in 1987.

I got called on by this very wealthy family from Hong Kong, overseas Chinese family, Dr. Hwang Chik Lim. Establishing himself in Hong Kong and in Malaysia, made his money in hardwood timber down in Sabah region of Malaysia.

Being an overseas Chinese, it was that early era when they just started to have those joint venture laws in China enabling outside money to come in. It was always party A and party B.

Party A was the Chinese government. Party B was sort of a sucker-overseas money. Because in those days, there weren’t very many rules about what worked in China.

So we did this phenomenal project in China, in Beijing that was an 800 acre site in Chaoyang district, which is the robust growth district on the east side of Beijing.

And it was called Shui Tuen Park, but it became Chaoyang Park. And we looked at building a theme park there and a lot of development in the public park and also a movie studio.

That was to be the ambition of the project. It became a very substantial development opportunity for Chaoyang District and a big public park.

But anyway, that opened the door for us to start to look at China. With some fits and starts, of course, 1989 Tiananmen Square, slowed the growth there. Outside development eventually took hold. And I would say that became a very big driver of our business, all of the history of the development in China.

First Europe, and then Japan, then Southeast Asia and China.

Won: I see. Well, now that we’re on that topic, how did you see China evolve as a destination for theme parks and theme park development?

Ray Braun: Well, they had a huge interest in having that kind of development. The real driving force for it to become such a pervasive development program in China, theme parks in general, is that it was a way for developers to get land.

They would come in with the promise of, we’re going to build a theme park. And it was cultural tourism. We’re going to promote cultural tourism to your city. Wherever it is. Any, all of the sort of very significant cities in China.

And there were the very aggressive real estate developers. And they would get land for a theme park, and sometimes they built the theme park, sometimes they didn’t, but they built thousands and thousands and thousands of apartments. Crazy.

Won: Yeah.

Ray Braun: But some chains grew out of that. OCT Town was one of the more aggressive ones. Fantawild. There’s a number of them now that mostly developed their own stuff. Unlike in the US where most of the chains in the US ended up acquiring other properties.

But it was this very robust real estate program that really drove it.

Won: In your view what accounts for which operators were able to survive and which kind of just fell by the wayside? Do you have any observations there? Over the last 30 years in China, some of the theme parks were able to survive and some just didn’t at all.

Ray Braun: Well, there were some very poor developments, very inadequate. And it was such a hot topic in China that just about anything was called the theme park.

Early on, they listed 2000 theme parks in China. And I saw a bunch of them. And they were like a few boats in a marina and a restaurant or something.

It was not what we would consider to be theme parks. So a lot of stuff fell by the wayside. The shortfall was very poor development, lack of economics, not really building the product that was sufficient. So, there was a lot of shoddy stuff.

Universal Studios

Won: As part of your work in China, I know that you worked on Universal Studios, Beijing.

Ray Braun: That’s a story.

Won Kim: Yeah. Could you talk about your involvement with Universal in general? They’re one of the top two operators in the world, and I think you have a great experience and background with Universal in general.

Ray Braun: Yes. I had a long history with Universal with ERA and ECA. Was probably our biggest client revenue-wise, all those years.

And that involved working, in the early days, with the projects in the US. But eventually we became the group that would do all of the work for the international development.

We looked in several locations in Europe, that was probably the first thing we did. Because Universals always wanted to be in Europe.

And then Beijing is a great story. Because Beijing, we were hired in, I think it was the year 2000.

It opened in 2021. Universal Studios Beijing.

We’re hired in year 2000 to look at totally separate studies, very complete extensive, comprehensive, detailed studies of Beijing and Shanghai.

And Disney was in the running, of course, we know… and they [Disney] focused on Shanghai. They looked at other places too.

But for Universal, we had two assignments, two big projects. One was in Beijing and one was Shanghai. And they were very focused on, and selected Shanghai.

There was still a sort of a secret competition between Disney and Universal. But they went down the road and tried to do the project and had selected a site, and there were two years of negotiation of who was doing what on it.

And then Disney sort of blocked the door, took the Shanghai market. It was always sort of a little bit of a race. So then we looked several other locations for the Universal park in China.

Including going back to Beijing and looking again. And at that time, Beijing, in 2008, 2009 maybe. And Beijing didn’t want to have it, they still considered Beijing to be the sort of the cultural jewel of China. So they didn’t want to have an American movie theme. So we looked in Guangzhou and some other places, and eventually came back to Beijing with the banner of the Beijing Tourism Authority as a partner. They were a partner earlier, but I think they just had somehow overcome this cultural dilemma.

And went ahead with the project. And so 21 year process.

Won: Why do you think it took so long? I mean, usually—

Ray Braun: Well, looking at five different sites and changing your whole thrust, the investment with partners, you don’t just do that on a heel pivot. It takes years to get a partner and a site.

And Disney got the Shanghai market, and so they were looking everywhere else, and they had to talk Beijing into it, and it took a while.

I don’t know all the ins and outs of course, but from what I could observe, it was a trying process.

Legoland & KidZania

Won: Well, in addition to Universal you’ve helped kind of create some of the concepts for operators like Legoland and KidZania. Could you talk about being at the birth of those as LBE concepts?

Ray Braun: Yeah. Well, I think it’s interesting, the evolution of LBE. First there were theme parks, which is the top of the pyramid of entertainment development projects. Because they’re the biggest and most expensive.

And in modern theme parks, they use IP and very important components like that. Theme parks really set the stage and a lot sprang out of that. They were certainly the model that led waterparks and the growth of various forms of LBE.

There were family entertainment centers, but sort of the transition to maybe more branded entertainment centers. Along the way, one of the two best models for a global rollout of LBE components, the best ones you can cite are [KidZania] and Merlin, with what they call their midway attractions. They have a bundle of them. Started out with Madame Tussauds, then they acquired Sea Life Aquariums. And then they had a deal with Lego for the Discovery Centers. And they’ve got several other things. They have the Eye. And several others. And I don’t know what they’re up to now, but they probably have 150+ units of those five or six products.

And we would work with Merlin. Before it was Merlin; Tussauds Group and Charter House. And then it was Merlin, they set up a very well run organization, having the theme park sector and the LBE sector as sort of a balanced portfolio. Well, we worked with Tussaudsand helped them be sold and rolled up into what became Merlin.

Then they made their deal with Lego so they ended up having two kinds of parks. They had Alton Towers, Chessington Thorpe Park, amusement parks in Europe. Then they acquired several others like Heide Park and Gardaland in Italy. Then they had a deal to develop the Legoland parks.

But I want to back up a minute. How did Lego get in the theme park business?

I was giving a talk in the anticipation early in 1990 or something like that. Euro Disneyland opening in ’92, I was giving a talk in the south of France to the European amusement community. And the purpose of the talk was, you should embrace Euro Disneyland.

Because it’s going to raise the tide. And you’ve got to invest and upgrade yourself. But it can benefit you a great deal, and expand the industry. That was the talk.

And after I gave my talk, there are six young Scandinavian guys, middle-aged and young. Came walking down to talk to me. And they were the advance team from Lego. And Lego had a little amusement park at their headquarters factory area in Denmark. And sort of evolved as a historical accident. People came knocking on the door and said, is this where they make Lego bricks? And can we see them? And so they made a little place for them. They grew to a little amusement park, and then it grew to a reasonably sized amusement park.

But they wanted to get in the business somehow in a more aggressive way. And we had several workshops and things about what it should be, should it be something mall based, exhibit-based or a theme park. And so we were part of the process to help them think, well, theme parks would be the way to go.

So we helped do strategy for them and how they would go about a roll-out both in Europe and the US and that led to a pretty robust product.

First new product was Windsor, and then Carlsbad. And went from there, we helped them put together the first foray into Asia, which was in Malaysia, the very southern tip near Singapore.

And yeah, my gosh, ECA is looking at five new sites, I think for Legoland in China.

So then they brought that in for the Lego toy company, actually got in a little financial trouble for a while, and they had to join up with Merlin for the development of the parks and operation. So they become paired up.

By the way, Lego has dramatically recovered their toy business. They are very strong and actually bought back some of the ownership of the park. So that’s a little bit of the Lego story.

The KidZania story is about a really amazing entrepreneur named Javier Lopez along with some partners down in Mexico City. Just on their own they built the original KidZania, at a shopping mall in Mexico City, Santa Fe, sort of an upscale shopping mall.

And they thought, well, maybe this has power beyond Mexico City. Actually I think first they had Buzz go down there and look at it. And then Buzz referred them to me. And I went down to visit with them. And we ended up helping them strategize their roll-out starting with the US, and then the idea to go international.

As it turned out they didn’t do the US rollout. They had a very interesting financing program. They thought that with KidZania they get this sponsorship of all the different activities that you do inside of the children’s theme park. Sort of career pavilions.

And so they thought they could get the sponsorship paid in advance and some tenant improvements from the mall operators, and they could finance it that way.

That didn’t really sell in the US at that time. So, Javier adopted a different strategy internationally. He didn’t try to do it on his own, he did it on a franchise basis. And so he first went to Japan and very successfully opened, got a partner in Tokyo and then little by little all over, I think they’re up to pushing 30 units around the world, trying to get into the US.

So anyway, I’m a great admirer of Javier and what he’s done. Invented a really great product. Been very successful with growing it up.

Yerba Buena Gardens

Won: Absolutely. Going back to what you were saying about seeing the evolution of LBE, could you talk about how you’ve seen the evolution of entertainment retail as well?

Ray Braun: Oh yeah. Well, that was a big deal. That was a big strategic move we made at ERA. We talked about the real spurt of building regional theme parks in the 70s and 80s. Well you sort of run out of markets. How many can you do? And so the industry was looking for the next product.

And at the same time commercial real estate was looking for things to differentiate and add to malls and create better, stronger visitation.

There were a couple formative projects that I worked on that really informed that push to blend entertainment with retail. One was called Yerba Buena Gardens. Started working on that in 1980. We were part of a group with the city to put on an RFP to develop a mega downtown urban project in San Francisco. It was between 3rd and 4th, between Market Street and Howard, now below three blocks and that’s where they built the Moscone Center, and they built the Moscone Center under our ground so we could build this Yerba Buena Gardens project on top.

And so we selected Olympia & York to be the master developer. It was the first urban renewal, urban redevelopment project that anyone was aware of, where the driving force was what we called C-A-R-E, Cultural Amusement Recreation Entertainment. Those were to be the drivers. Of course, there was a 1500-room Marriott Hotel. And 800-room other hotel, and a million and a half square feet of office buildings and things like that.

But the rest of it was park and entertainment zone, which eventually became the entertainment retail piece, eventually became the Metreon.

Sony Pictures, which had missed out on the theme park boom was adamant about being in the business of entertainment retail. The next wave.

So they [Sony] brought in people from Disney and they did the Metreon, they did Potsdamer Platz in Berlin. And I think there’s a third one.

I was on the selection committee for the city to pick who would develop that piece of the project. There were two final bidders, and I was actually an advocate of the other bidder which was a real estate developer because their approach was 350,000 square feet of commercial space downtown, a fabulous market. To find 350,000 square feet of people who were in that business – of tenants, who were the best to do those things.

Sony’s approach was 350,000 feet of development opportunity in downtown San Francisco. Let’s figure out 350,000 square feet of new things that we can develop and new traction ideas. And of course they had the movies and some restaurants and stuff. They tried to do a lot of new attraction ideas that were unproven and ultimately didn’t very well.

But anyway, those kind of projects were happening.

Blockbuster Park

Another one I could mention would be Blockbuster Park. Blockbuster Entertainment Company was in the early 90s was owned by or run by Wayne Huizenga. Amazing man, maybe the only guy I’ve ever heard of to create three Fortune 500 companies. First was Waste Management, then was Blockbuster, and then it’s called Republic Industries. It was an amalgamation of several different companies.

Won: Wait, so this was Blockbuster the video rental company?

Ray Braun: Yeah. Wayne Huizenga was a very smart guy. He saw the writing on the wall. That streaming was coming eventually, or having a store with these boxes wasn’t going to last forever.

So, he was looking at other things. At the time he owned the professional sports market in south Florida. He owned the Miami Dolphins. He owned the Marlins baseball team, and he owned the Panthers hockey team. And he wanted to build a new arena. He didn’t own the basketball team, that was Micky Arison. But he owned the other three teams.

And he wanted to build a new baseball stadium, he wanted to build a new arena for the hockey team. And he also owned Joe Robbie Stadium, which is where the Dolphins played.

I worked with him to look at how to do that. He had all these ideas about how you blend sports with other forms of entertainment and retail, as an anchor. His idea was people come early to the game, stay late after to have a drink or something. And it was sort of like an expanded fan fest idea. It was his notion.

But we looked at it and said, the place to do that is not Joe Robbie Stadium. There wasn’t enough land. And it wasn’t ambitious enough and may not have been the best part of town to do it. So eventually, he started to buy a 3000, 3500 acre property right at the border between Dayton, Broward County adjacent to the Everglades.

And we did a lot of planning on what we called Blockbuster Park. And it would have a baseball stadium, a big arena, a huge entertainment retail place, and a lot of hotels and golf courses and Olympics facilities and all kinds of stuff. It was really a very ambitious project.

Then you may remember what happened with Blockbuster is that, Wayne got pulled in with Sumner Redstone when Sumner Redstone’s National Amusements wanted to buy Paramount and Viacom and then Blockbuster. It was a big mashup of these different companies to buy Paramount and Viacom.

And Wayne thought he could get out of doing that deal, but he ended up doing that deal. Because he always wanted to sell Blockbuster.

It’s a more complicated story about how that went down. But he did eventually have to give up the Blockbuster Park project, because Sumner Redstone looked at it and said, so why do I want to build this? These stadiums and stuff, who owns these teams? And he [Wayne] says, well, I do.

Why would we want to build all this stuff for you and your teams? They had to walk away from that project.

So it didn’t happen, but there were a lot of people from the industry, our architects and stuff. We had big, huge planning sessions with just about everybody and there was a lot of interest in this topic of how do you blend entertainment with other things, other anchors.

Disney was doing it with their Downtown Disney and Universal had Citywalk. So they had the theme park anchor along with entertainment retail.

But why can’t we anchor retail with these other things like sports, all kinds of other anchors. Which led ULI (Urban Land Institute) to get interested in the topic too. And there were a couple books that I contributed to about building urban entertainment centers. There was (in the 90s) a real active interest in UEC, Urban Entertainment Centers. I think I had a sidebar in that book about acronym soup, we called it a lot of different things with different initials.

But it was a very hot topic. And I was part of founding a council within ULI for entertainment development. And then ULI did a conference every year about entertainment development. And one year it was in Beverly Hills, the Beverly Hilton. Then it was the next year at the New York Hilton. A lot of interest in how do you do that.

It led to a lot of other projects. I mean, one of which we could talk about is LA Live. Which was probably the best combination of entertainment with sports anchors. Well, two anchors.

The Convention Center was right there next to it. So that was also an anchor. So we worked on planning that from the beginning. There became a real momentum to that type of development.

Won: That Blockbuster Park project. It brings up a point, which is that, you must have seen probably thousands of these projects that have been planned, since the beginning of your career. Are there any other memorable ones; ones that have either been built or ones that you would’ve liked to see been built, that weren’t.

Ray Braun: Well, that’s one of the interesting things, is sometimes the stuff that doesn’t get built could’ve been super interesting. Blockbuster Park would’ve been super interesting. If it would’ve happened, it would’ve led to Wayne buying out the Paramount Parks, that was part of one of the equations. Because he liked the theme park business. Sometimes you learn by your failures more than your successes.

But I think Blockbuster Park certainly was, I think Metreon was a kind of a missed opportunity because it wasn’t a straight ahead retail entertainment development. It sort of helped somebody (Sony) try to join the industry. Which they’re doing now, by the way, with IP, but that’s another subject. The group that’s handling it now is having some successful rollout with IP products in the LBE industry. So the question was a favorite…

Won: Yeah. Just any favorite or memorable projects that you’ve worked on that have either been built or not built that you’d have liked to see built?

Singapore & Malaysia

Ray Braun: There’s a couple of good stories. I mean, I really enjoyed working on Fiesta Texas in San Antonio, which ended up becoming part of Six Flags. Was originally a joint venture of a big insurance company, USAA. They owned the land based in San Antonio.

And they had land as an operator, and it was this quarry site, very unusual, what the hell do we do with this site? That was very fun to plan because it was kind of a unique development.

I think I’d like to talk about a couple things, but development in Southeast Asia I’ll tell you a story about. Well, Singapore and Malaysia. Southern Malaysia is kind of an extended market area. And I looked at Singapore for many, many different groups because it was a very attractive marketplace. And there was no way you could develop a theme park because no matter how bad Singapore wanted it, eventually it would go back to the Urban Development Authority and they would say, okay, you want 200 acres. It’s $200 a square foot for the land or something. And kill any theme park.

But finally we were working with the Singapore Tourism Authority which is a very progressive group, by the way. Eventually came up with this idea of how do you extend tourism to Singapore? And one of the big notions, of course, was casinos. You didn’t say casino, the word casino, you said integrated resort.

And that led to two projects being approved. One project was to have bolted into it, a lot of family entertainment. And the other was to have big convention facilities. Marina Bay Sands was granted the rights for the property in Marina Bay. Las Vegas Sands, property in Marina Bay.

And that had a million square foot convention center and a great shopping center and stuff too. And other thing is changeable cultural attraction.

And then the second site was Sentosa Island, given to the Malaysian group Genting, which had a casino up in Kuala Lumpur. And they recruited Universal Studios to build a theme park. Just a license. That’s the only one that Universal did as just a license. And it’s a very compact site for Universal. It’s unlike the other Universals.

But it’s the only way you were able to get a theme park built in Singapore, is bolted onto a casino project, which the economic engine to get it to work. Right?

So that was interesting because it involved a real farsighted tourism development strategy. The other big tourism development strategy we were all involved in was Malaysia, the adjacent country. We started working with the big sovereign wealth trust called Khazanah, for Malaysia. There’s another controversial sovereign wealth trust that was pretty bogus in Malaysia, and you’ve probably read about it. It was a way for certain people including the former president to take a lot of money out.

But Khazanah is very super legit. I mean, the best and the brightest in Malaysia. We helped them figure out a tourism plan. Because they owned this huge several thousand acre property in the south, or 20,000 acres, I think, at the very southern tip, just across the causeway from Singapore. And they had all these grand plans for that.

There’s an example of things that we wanted to make work. We wanted to make Singapore and Southern Malaysia a kind of a theme park cloud. That was the big picture. So we got Legoland in there. And we were talking to Village Roadshow and a bunch of others about projects in that southern section. And even Disney to look at that section.

And these projects, we set in detail with a lot of planning, did a lot of design work. We got Pinewood Studios out of England and Legoland and some other development there. But the vision was for it to be quite a bit more.

Won: I see.

Village Roadshow / Gold Coast

Ray Braun: There’s one interesting story about the theme park industry in Australia. In the heyday of development in the ’80s in Australia, there were several property developers that just went up like a rocket.

One was called Ariadne, they had a 500 acre property just above Surfer’s Paradise in the Gold Coast of Australia. And so I started working with them to figure out what could be on that property. And they were starting a deal with Dino De Laurentiis, who was a movie producer. And he had built a studio in North Carolina.

And they wanted him to build a studio in this property, down outside of Surfer’s Paradise. And so we did planning. Okay, let’s do a studio park next to it.

What would that be? And how would we do that? Because it was just sort of a barebones studio, right? And we started planning that.

And then Ariadne, which as I said, went up like a rocket, also came down like a rocket. And that was the end of that.

At the same time, I was doing a lot of things with Warner Brothers. I was talking to Warner Brothers about this and they knew about it, this deal in Surfer’s Paradise.

And they had a relationship with Village Roadshow. So they got Village Roadshow to look at that property and Village Roadshow and Warner Brothers ended up building Warner Brothers Movie World in Australia. And Village Roadshow went on to buy SeaWorld, and made a theme park group. They’re very active in a lot of different markets.

So that was sort of interesting how that came together, sort of a backdoor story.

Won: Yeah. That is. So what happened, that land was owned by Ariadne, and did it just go over to them? Did it go over to Warner Brothers?

Ray Braun: Exactly what details that Village worked out to get control of it I don’t know. They built a park.

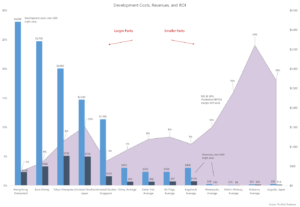

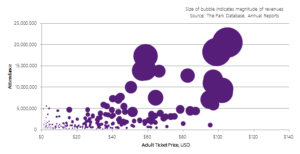

Another interesting story. The study for that said, in those days, these are different, these are old numbers – you could build a park for a hundred million dollars and get a million people. You could build a park for $200 million. Because the market was only so big, you could get a park for $200 million, you get a million one (visitors).

Ray Braun: So they built a fairly modest park.I mean it’s grown over time. Still, Australia is a limited market. It gets about a million five.

Success Factors

Won: As you look back over all of these projects, is there anything that sticks out to you in terms of lessons learned from either the successes or the failures, what to do, what not to do for developers or anyone in the theme park or entertainment industry?

Ray Braun: I mean, there’s so many lessons, Won. I don’t know where to start.

Just to talk a little bit about what it takes today. What’s really important today is a few things. One is compared to the early days, the sophistication of the product, the influence and the importance of intellectual property usage. How do you do that?

Getting the right deal and having branding power. That’s something we talk about a lot.

Of course there’s bigger and badder coasters. Much more immersive things and interactive, both in theme parks, but also in LBE, with all of the immersive art projects, “art-tainment”.

All of that is so pervasive now. So you got to know how to work with that. And you have to have your eye on that at all times.

I mean, there are certain things that are just givens now. Anything you develop now has to be planning for the next generation of tech.

And there’s all kinds of things in terms of ticketing and do you even have a gate in the future? Epic Universe for Universal might not even have a standardized gate.

So there’s sophisticated programs for dealing with that and gamification and all that entails.

And personalization, mass customization, right? All those things are just critically important. It is no longer a debate to say that you’ve got to be planning on technology. Sustainability is the other given, right? You have to be the best you can be in all of that.

Another thing that’s super important is that we’ve learned that Walt taught us back in the 60s, but we didn’t pay attention, was that it’s much more economically strong to build a destination than just a project.

And if you look at, I mean, it really is all about destination creation now. So if you’re talking about a theme park, how do you extend that? Well, the standard formula is you need two gates so that the customer perceives it’s a weekend or it’s a multi-day visit. You need something for people to do when it’s not during the daytime when they’re in theme park.

So you need the entertainment retail component, and you need to have overnight accommodations so that you capture that, as I said, several days versus several hours. Dramatically different when you do that. However, dramatically more expensive.

So the other given today is any of these projects are of such scale that they must be public-private partnerships. It’s just billions of dollars. And a great story for the local government in terms of job creation and impacts and image and tourism to this area. It is a great story to tell. If you really are building these mega projects, you have to be very upfront about telling a story.

Won: Understood.

Ray Braun: Those are very powerful trends right now.

Won: Great. Okay. I think we covered a lot here.

Getty Center

Ray Braun: The only thing, the topic we you and I discussed that we might want to touch on would be cultural stuff.

There’s a couple of cool stories. Maybe the most notable cultural project that I worked on for 10 years, was the Getty Center in Los Angeles.

And what was interesting about it was they had $8 billion in the bank when I first started talking to them. They’d hired Richard Meier as their architect. They bought that 800 acres in Brentwood, expensive real estate in Los Angeles. So the issue wasn’t feasibility. And they wanted to make it free.

They were going to spend a billion dollars in those days on this project. This is the late 80s and 90s. So we were working on it. What we were brought in to sort of be the watch out, be the guardian of the visitor experience.

And Richard Meier, brilliant architect, and his team were laying it all out. And they had a scheme for how it worked – progression, the historical progression of art from the Renaissance to more recently, and they had these different pavilions that progression would take place as you went from building to building.

Then there’s things like, well, we want it to be a good visitor experience. So, we don’t want the visitor to wait more than five minutes for anything. And so we had to find out where the bottlenecks were and stuff like that.

So we built several models, we ran it 50 or 60 times, we built a big visitor simulation model; how would people proceed through the place? How long would they stay, where the dwells were, how all the different galleries and the different activities. And that was really fun. That was different.

For us it wasn’t feasibility, as I said. It wasn’t market research. It was how do these things work? And so during the course of that, sitting at the table and planning and everything.

So the museum itself was going to be pushed on top of the hill, 800 acres, but it was all hillside. They gave 780 acres back to the city. Because they just needed to be down at ground level and then up on the top of the hill for the facilities, ground level for the visitors arriving in parking and stuff like that.

Especially, how are we going to get about three quarters a mile from the parking up to the top, how are you going to get that? And how are you going to get people up? And we talked about that. The best answer I got from him was, well, we’ve got this roadway. We’ll drive them on buses.

I said, you can drive smelly old buses, but in this billion dollar best museum in the world place, that’s not going to work. I said, well, let me bring somebody in.

And I knew this guy who was the west coast guy for Intimin rides. European ride company, but he was based in California. So I brought him in and introduced him to them and said, Intimin got their start in Europe building funiculars up in mountainous areas. So, can we build a funicular? It’d be great.

And the Getty people were shocked because they were very art people. And they thought that was Disney, a bad word.

But eventually it made so much sense that it came around and so now we had the funicular. That’s a notable part of the Getty experience.

Won: Yeah absolutely.

Ray Braun: That was fun. California Academy of Sciences maybe. So how have we been involved in cultural projects, museum projects?

Well, the truth is, the Getty was an outlier. Because we don’t usually get involved in art museums. Art museums, by and large across the country, have economics based on contributions.

But other things like science centers, natural history museums, things like that are much more visitor experience-oriented and earned income-oriented compared to contributions, and becoming more so. More and more of the industry is creeping into those kind of products. So we’ve actually always been more involved in those kind of projects.

So, one of which was California Academy of Sciences in Golden Gate Park in San Francisco. They had an old tired facility that was really these different buildings that have sort of been built on top of each other to get to 400,000 square feet or whatever it was. I think there were 17 or 21 different buildings that are sort of bonded together.

And they’ve been rattled in over a number of years in earthquakes, so they had to really redo the whole thing.

I got involved in the project to plan that. And they brought a famous architect in Renzo Piano to build a spectacular building. Which highlights another thing in the museum cultural businesses, that a lot of times museum boards get infatuated with star architects.

And the building and the look of the building becomes more important than what happens inside. That’s something you really have to be careful with.

Because sometimes you get these extraordinary buildings and the museum isn’t much. So with the Getty, I told you our focus was on what happens inside. And same with California Academy of Sciences, besides doing the overall numbers for the place, you come with a big expanded facility. We did a lot of work on trying to develop the program. How does that work? They had to close things down for a couple years, and so they had to build a temporary museum somewhere. And how would that work?

Won: Yeah. Going back to the Getty, how was that work manifested? You tried to figure out crowd control issues and spacing people out. In the end was it a matter of just spacing things out more? How did they actually reflect your recommendations at the Getty?

Ray Braun: Well, it had to do with flow. So I think going upstairs and stuff can be problematic. So you got to be careful how you do that.

But the alignment it had, it changed, because we were part of the planning team. It changed some of the alignment of how you progress through.

There’s two Getty museums. One is the Getty Villa out on the coast in Malibu, and then there’s this one. The coast is antiquity, so it’s up to the Renaissance. And Getty Center, the one that we’re talking about is Renaissance forward. So there was a building for the Renaissance, and then there was 1600, 1800s focus. And then there’s decorative arts, and then there’s the more modern. So it had to do with how do you pace people through the building?

Won: I see.

Henry Ford Museum

Ray Braun: I’m a little foggy on all of the answers too. Tweaks that we did. It was really fun to be part of planning that process and its brilliant development with that outdoor garden. Spectacular stuff.

One other thing that I would say was that, maybe this is a category of didn’t quite happen but what we thought was a great opportunity is the Henry Ford Museum in Greenfield Village in Dearborn, Michigan.

So we went in with the team to look at the Henry Ford Museum, which was a classic museum. Henry Ford was an amazing acquirer of objects and things. In the Henry Ford Museum, he had of course, all kinds of cars, but also steam engines and all this other stuff in the adjacent outdoor park, outdoor historic park where he had rebuilt things. And he actually bought these homes and buildings and stuff, sort of recreated them.

And so we were looking at those two sort of big, how do you make them better? And Matt remaster plan something like that. But also during the course of that, we started talking with them about third attraction, which was they were rebuilding the famous factory site called the River Rouge Plant. The postcard for World War II, industrial America with big smoke stacks, belching. That stuff. It was classic. They brought in iron ore on the river, and then they processed it on one side, and out comes a car on the other side.

But it was being rebuilt, as I said, an environmental disaster. It was being rebuilt as the cleanest factory in the world. And Ford had hired this famous environmental architect guy to do it. And then they did this remarkable job of capturing everything. So we ended up being asked to figure out how do we tell that story? A visitor center and a tour and stuff.

One of the big ideas we had was, Detroit doesn’t really have a theme park and it doesn’t have any big strong visitor attractions. Not like other places. You could bundle these three things together and make it sort of a cultural destination. Because they had some additional land. You needed some of those other destination components, hotels. And I thought that was really a great opportunity.

I was hopeful that we could do something with that, because we were also working with Ford at the same time on what became Ford Field, the football stadium downtown Detroit. In those days it was a pretty rocky place. But they were building the Comerica baseball stadium next door to the site from Ford Field. And then a couple walks away was a big indoor concert theater place. It was being refurbished.

And we thought could we build a whole district around that and tie it together via redevelopment and rehabilitation. And the other, there was a pizza guy that was making some of the investments in some of that downtown there – Little Caesar’s Pizza. But I guess the Ford family and they didn’t get along that well or something, but we had a scheme to make a whole district out of that.

And I thought that was a really good idea. Again, one of those things that didn’t quite come together until more recently, matter of fact about four or five years ago, I was back in Detroit for a ULI meeting and they built the hockey arena, had started to redo this whole district. So hopefully it’s coming together now.

Won Kim: Yeah. I’ve been in your shoes many times as well, where you make a lot of recommendations to the client, or you present the findings and it seems there’s this big disconnect between the results and findings and what they actually end up doing. Do you think it’s a lot of times just because it’s kind of too far ahead of its time or do you have any insight into why that happens? Why it doesn’t actually happen the way?

Ray Braun: It’s probably a different story every time. Sometimes it is a little too much. The big picture might be a little too much to bite off, so you needed to be able to stage it.

How do you eventually get there? Sometimes the market isn’t quite ready for it. And then deals change. It’s real estate. So deals change and people exit and go on.

Being in this business, I’ve always enjoyed, as economists, the opportunity to get a little bit creative about what could be done. And sometimes it works. But I mean, for me, that was the most fun part of the job, was not just cranking out another, okay, you’re going to get 2.2 million people to come to your theme park. But if we did all these other things, it could be something bigger or better.

That was really fun. But as you know, in this business, we get calls from people who have an idea, have a big idea. Maybe they don’t have much else behind that. You sort of have to hear them out.

See where it goes. I get all kinds of wild ideas. Sometimes they’re crazy. Sometimes maybe you could see the way how they could work with a little readjustments. But I always think you need to take the call. All those people, because maybe there’s next Walt Disney out there.

Whole brand new idea, something crazy.

Won: Yeah, exactly. Any other parting thoughts or comments?

Ray Braun: No, I think we covered the topics that we had hoped to more or less. I enjoyed talking with you and it’s been a fun go of my 53 years for me in business.

Won: Well, maybe we could do a part two sometime and maybe drill down a little more deeply into some of these projects. It seems like we covered a lot of these in a very short amount of time.