Table of Contents

ToggleAt its height, Evergrande Group was the largest real estate developer in the world, with contracted sales amounting to more than 700 billion RMB (~$100 billion) in 2020, and a billion square feet under construction at nearly 800 projects around China. Appropriately for its ambitions, Evergrande was also in the stages of building theme parks and tourism resorts on a scale larger than any that had ever existed.

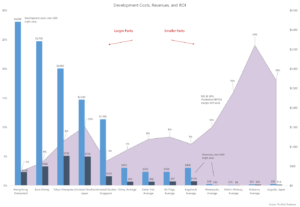

In 2020, the company was in the planning stages of more than $40 billion in theme parks and waterparks. As a point of reference, the Disney Shanghai Resort, the single costliest park to ever open, had cost less than $6 billion just a few years before.

Unfortunately, the group was overextended. As China shut down during the pandemic, all but turning off its real estate industry, Evergrande began to default on its nearly $300 billion in liabilities, earning it an entirely new distinction as the world’s most indebted real estate developer. The company de-listed its stock from the Hong Kong Exchange and entered a court-ordered, debt-restructuring process, and forced liquidations of its assets.

In Evergrande’s story are the outlines of the Chinese real estate industry writ large, from breakneck growth, staggering ambitions, and a curious, little-understood emphasis on theme park development.

While Evergrande and its peers eventually came crashing back down to earth, what can’t be understated is their role in a real estate construction boom and theme park mania the likes of which had never been seen before.

The Importance of Real Estate

The story begins in the 1990s, when market reforms liberalized the housing market in China. Homes were sold on the market for the first time, rather than obtained through one’s place of employment.

Over the next decade, the right of property ownership was constitutionalized and formally legalized, and real estate quickly became the asset of choice for the Chinese population. The stock market was volatile, with the characteristics of a gambling machine. The country lacked a social safety net, and inflation quickly ate away at bank deposits.

Homes, on the other hand, both appreciated in value and had the additional benefit of being actual domiciles to live in. They had a cultural importance too – having an apartment was looked upon as a prerequisite for a man to be eligible for marriage.

Annual volumes of land sales quadrupled between 2000 and 2009, from 49,000 hectares to more than 200,000 ha (more than 500,000 acres) per year, representing a nearly 20% annualized growth for a decade.

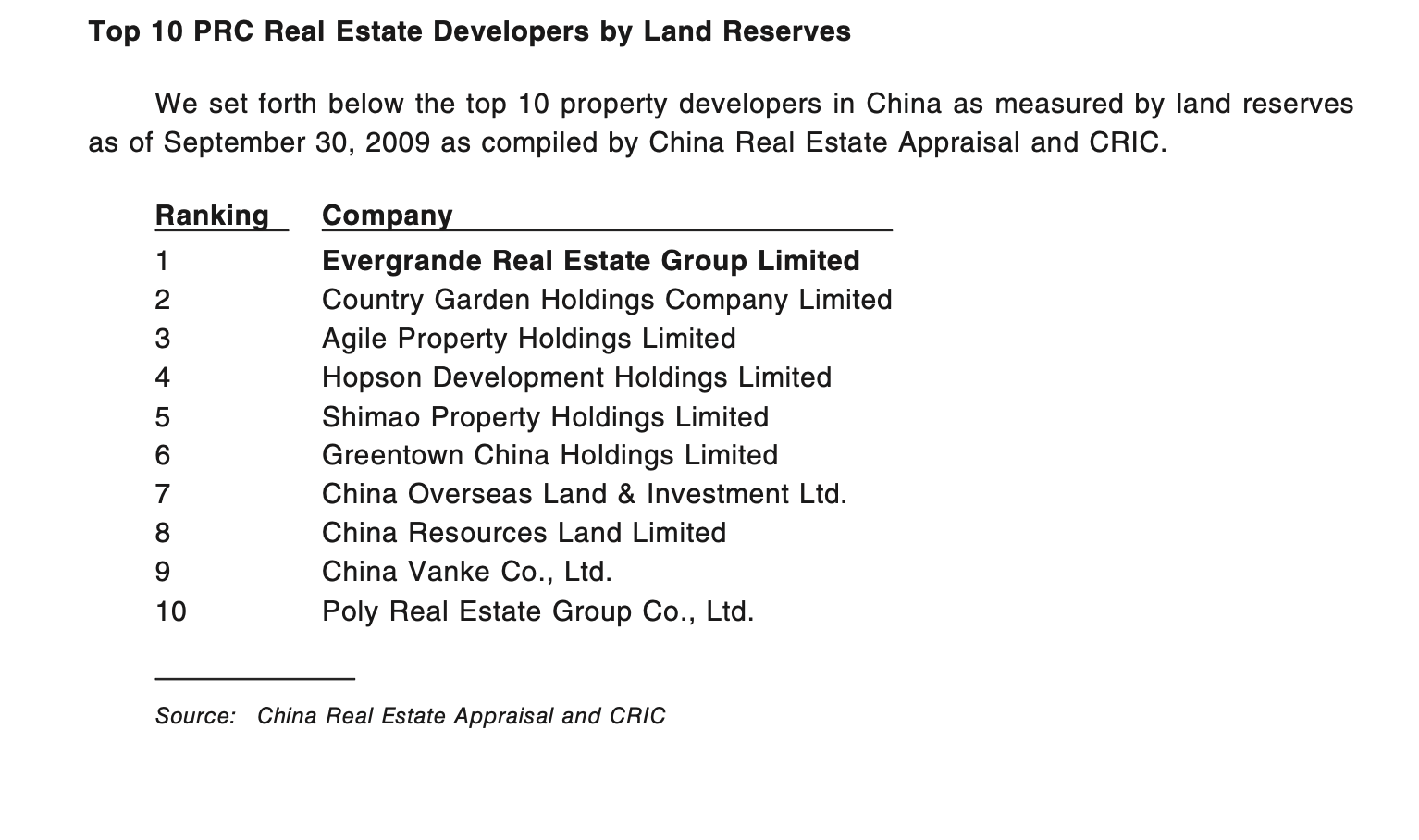

Evergrande debuted on the Hong Kong Exchange in 2009, scarcely 12 years after private ownership of property had been introduced. It had completed more than 4 million square meters (44 million sf) of property development, with more than 40 million square meters (440 million sf) of additional properties under development. By the measure of its land bank, which was over 500 million sqm in size, Evergrande was already the largest real estate developer in China.

Already in 2009, Evergrande’s size was staggering, but its prospectus seems almost quaint in retrospect. It was a pure play real estate developer, in the business of residential real estate only, building villas, townhouses, condominiums, and high rises.

The company had three product lines: a high-end series, a mid-to mid-high end series, and a “tourism-related series” under the banner of the “Evergrande Splendor” product, a mix of residential and resort elements, with hotels, commercial, and conference facilities. In the existence of this “tourism series” were hints of what was to come.

The Importance of Cultural Tourism

After its IPO, business boomed for Evergrande, and boomed for the rest of the country too. China made it out of the Global Financial Crisis unscathed, driven by what was (at the time) an unprecedented fiscal stimulus of more than half a trillion dollars (4 trillion RMB).

For the next decade, real estate and construction-related industries would account for an increasingly large share of China’s GDP, reaching a peak of nearly one-third of all economic output. The country turned into a construction zone. Apartment flats were built in a matter of months, subway lines and bridges and airports arriving by quick delivery.

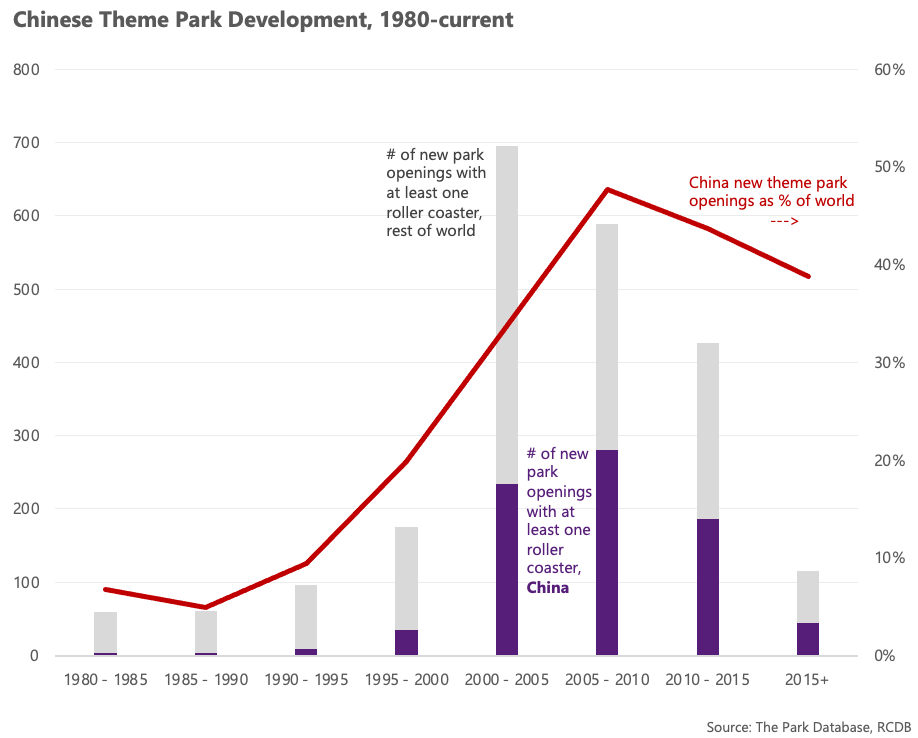

Theme park development was booming too. In fact, theme park development had been booming for almost twenty years, ever since the early success of Shenzhen OCT.

Enter Theme Parks

Started in 1985, the Shenzhen OCT master plan development was an experiment by the state-owned Overseas Chinese Town to draw visitation to Shenzhen by creating tourism destinations.

By the early 1990s, the Shenzhen OCT zone had opened the Splendid China Folk Village and Window of the World miniatures parks. Widely recognized as the country’s first “theme parks”, the attractions allowed guests to visit the major landmarks of both China and the world in “just three hours”, with replicas of the Great Wall, Taj Mahal, Eiffel Tower, pyramids, and other famous places.

They were centerpieces to lushly landscaped master-planned grounds with gardens and pedestrian walkways, and rows of residences. The apartment blocks were a hit, due to their location, and the theme park even more so.

After receiving a flood of visitors, and paying back its investment capital within a few short years, OCT rolled out two more theme parks in quick succession, one of which was Happy Valley, the first of the now-ubiquitous ride park chain.

Shenzhen OCT became renowned nationwide for its success, which in retrospect was as much due to its master-planned, long-term groundwork as it was to just building novel land uses like theme parks. In fact, OCT had originally been widely ridiculed for spending six months just on the landscaping of the grounds, a timeframe during which entire city blocks could have been built.

In the minds of real estate developers nationwide, however, theme parks and residential real estate became inextricably linked.

So much so, that the history of Chinese real estate can’t be understood without understanding the role of theme parks, or these “culture tourism products”.

Theme Park Frenzy

As a relic of its history of central-planning, China’s government was used to setting targets for GDP growth, and the local governments were used to hitting them by any means possible. After private ownership of real estate was formalized, local governments began hitting these targets by increasingly resorting to…land sales.

At their peak, land sales accounted for up to 40% of local government revenues, the single most important source of revenues – even more than local taxes.

Land auctions were the focal point, the beginning, for the single most important segment of Chinese economic activity, which was real estate and construction. Unfortunately, these frenzied land auctions became riddled with corruption and opaque practices, one that the central authorities began to struggle to contain.

Theme parks took center stage. Following OCT’s lead, real estate developers differentiated their bids by promising theme parks and “culture tourism products” embedded amongst the blocks of residential real estate. Such promises were a win-win situation – promising theme parks allowed real estate developers to acquire land at sub-market rates, while local governments were happy to receive such “culture tourism” products.

Not only would a theme park have the optics of giving something back to the people, whose ancestral lands were being sold to the forces of modern development, such “cultural tourism products” promised to draw visitors from far and wide, and be an economic engine with ripple effects across the entire economy.

In between the lines, however, problems were emerging. Allegations of graft, cost stuffing, fraudulent loans, and outright bribery plagued the entire process, and moreover, everyone was discovering that while Shenzhen OCT was a great model, there was only one Shenzhen OCT.

Developers who won the bids lost interest in operating the parks once they were constructed – if they were even constructed at all. A theme park, to be operated over the long-term, with long-term phases of reinvestment, had no appeal alongside the lightning quick, astronomical profits one could earn on selling apartments and villas instead.

All across the country, theme parks lay in states ranging from vacant land to half-finished construction, to built-but-not thriving. Already by the end of the 1990s, over 90% of the 1,000 theme parks dotting the country were unfinished, while thousands more were underway.

Scandals riddled the country. In Wuning, a theme park occupying 3 million square feet of prime city center land, was promised in return for the rights to commercial development. While the World Trade Center office tower was eventually built, construction on the theme park never proceeded much beyond land excavation. When rains flooded the site, creating irresistible pools for local kids, three children tragically drowned.

After nearly two decades of fast and furious theme park-real estate construction, the authorities had had enough. In 2011, the State Council declared a moratorium on theme park construction, blasting the “blind construction of theme parks” that riddled the country. In addition to the suspension, each city was to generate and submit a list of all theme parks that were planned and under construction.

For the next two years, theme parks were off the table.

Theme Park Frenzy, Part II

In 2013, the theme park moratorium was lifted, with strict requirements for development. Theme parks could only be constructed after “careful evaluation”, such as feasibility studies, and could no longer be bundled into general real estate master plans.

By this time, an entire generation of real estate developers had grown accustomed to thinking about theme parks as a necessary part of any master plan.

The 2013 clarification set off another boom in theme park planning. Developers read the State Council’s clarifications carefully, and began planning them more meticulously, bigger, better, and more unique.

Over the next few years, a flurry of extravagant theme park announcements were made by Evergrande’s peers, including Wanda’s famous pronouncement that it would run Disney out of China by investing in 13 theme parks at the same time, investing $47 billion to do so.

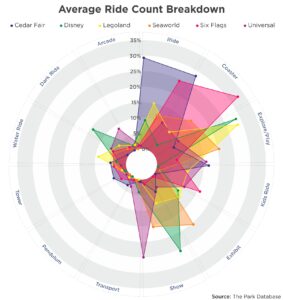

Zhonghong Holdings announced, among other things, billion-dollar theme parks to be based on the story of Journey to the West, and a 20% equity stake in US-based Seaworld. Similarly, Riverside Investment Group announced a partnership with Six Flags to roll out no less than six branded theme park resorts, with $40 billion in total investment. Seemingly, every major IP found a Chinese partner to develop a theme park based on it, from Paramount, Fox, Dreamworks, Lionsgate, Nickelodeon, Ferrari, Sanrio, Sega, and others. At one point there was even a theme park to be based on Lionel Messi.

Evergrande’s Ambitions

Evergrande’s “Cultural Tourism” segment had existed for decades. At the time of Evergrande’s IPO in 2009, Cultural Tourism accounted for 20% of sales, and consisted of residences that were supplemented by resort-like amenities, such as large pools, gardens, and other landscaping.

Like all of its peers, Evergrande had never been in the business of theme parks. And like all of its peers, this reality didn’t deter its ambitions.

In 2015, the company made strides into the cultural tourism business by commencing work on what would be one of the biggest private real estate developments in the history of the world.

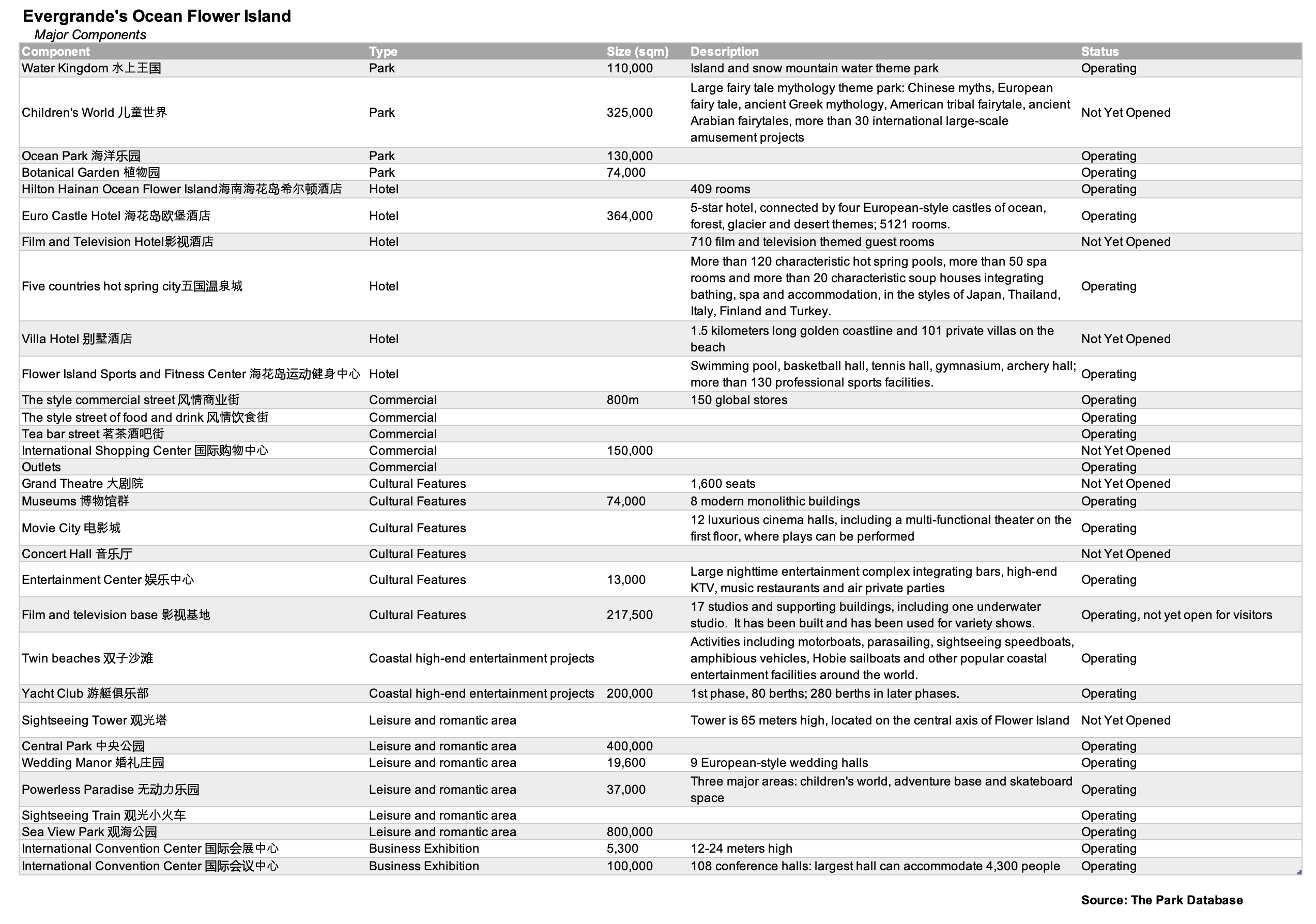

Evergrande announced the $25 billion Hainan Flower Island development, a 500-acre, man-made island sculpted off the coast of Hainan to resemble – you guessed it, a flower – with a theme park, waterpark, botanical garden, hotels, convention center, all surrounded by luxury apartments and villas. It would be nearly 10 times the size of any other Evergrande development.

After commencing work on Flower Island, Evergrande doubled down. In 2017, Chairman Hui Ka Yan declared that Evergrande, too, would enter the theme park business in zest by building no less than 17 theme parks and 20 waterparks all across the country, more or less at the same time. It announced the standard size $40 billion budget, and declared that such development would be led by multiple Fairylands and Water Worlds.

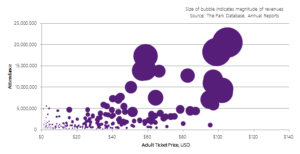

Fairyland would be a theme park designed for children and teenagers, based on fairy tales, mythology, Chinese culture, and history. It would be an all-indoor park, with 33 buildings each housing a large-scale amusement programs, for 33 attractions in total, which Evergrande boasted was 1.5 times the scale of an average Disney park. Each park would be located in a market surrounded by at least 80 million people, and thus attract 15 to 20 million visitors annually.

Evergrande Water World would similarly be a world-class, all-indoor hot springs waterpark and entertainment complex. The park would have more than 100 water “entertainment programs”, such as the world’s largest wave pools, parent-child “water cities”, artificial beaches, water walls, world’s largest drop slides, world’s longest indoor rafting rivers, and world’s “most exciting water roller coasters”.

Rounding out the theme- and waterparks would be all-around cultural tourism destinations with hot springs, ice and snow parks, commercial streets, convention centers, museums, and hotels.

Operating Realities

As you might imagine, there were several challenges to Evergrande’s ambitions.

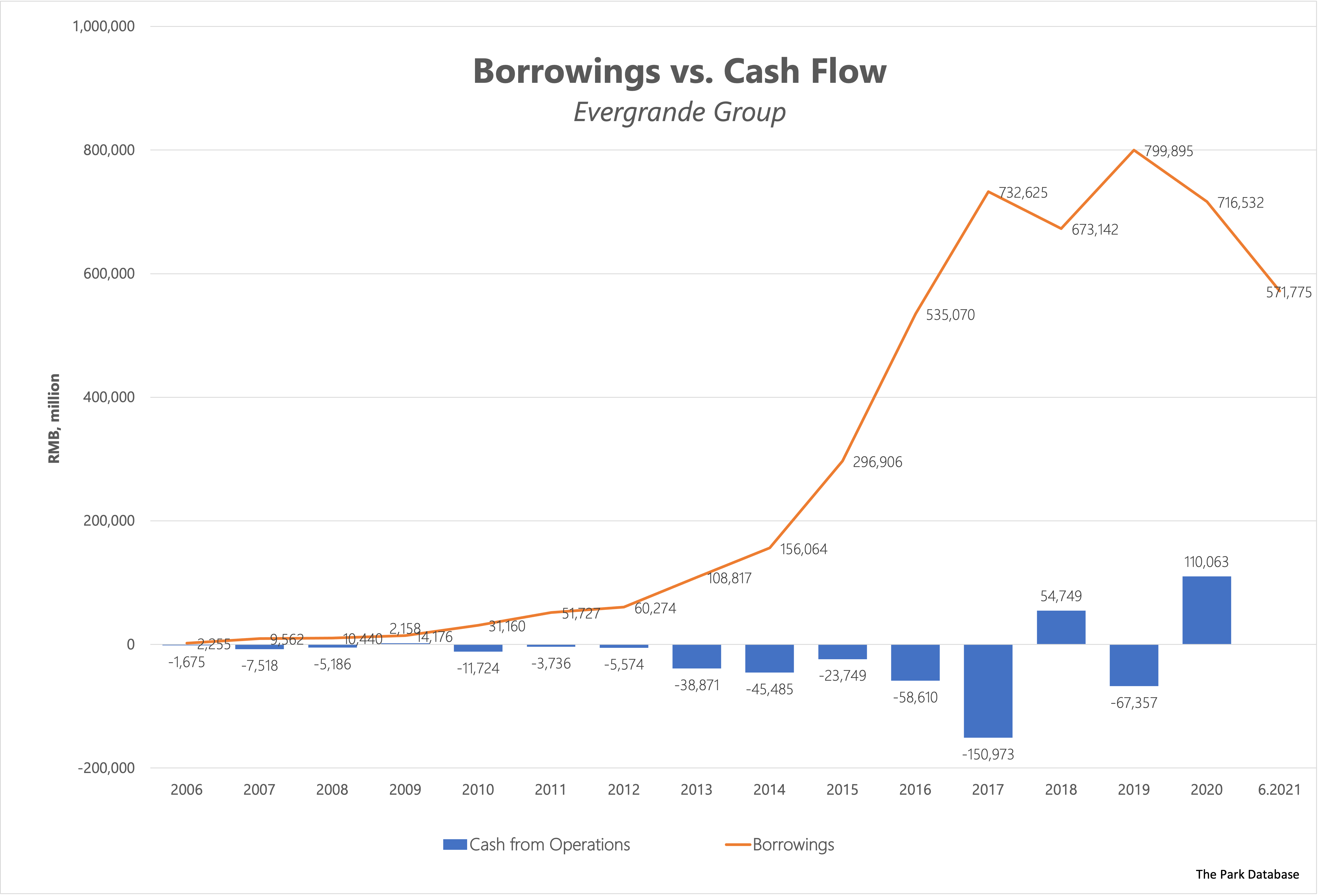

The first was a matter of finances, and it would be the one that ultimately derailed its plans. How Evergrande operated was no different from any other developer in China. This world-building on a scale that had never been seen before was all financed with debt. Lots of it.

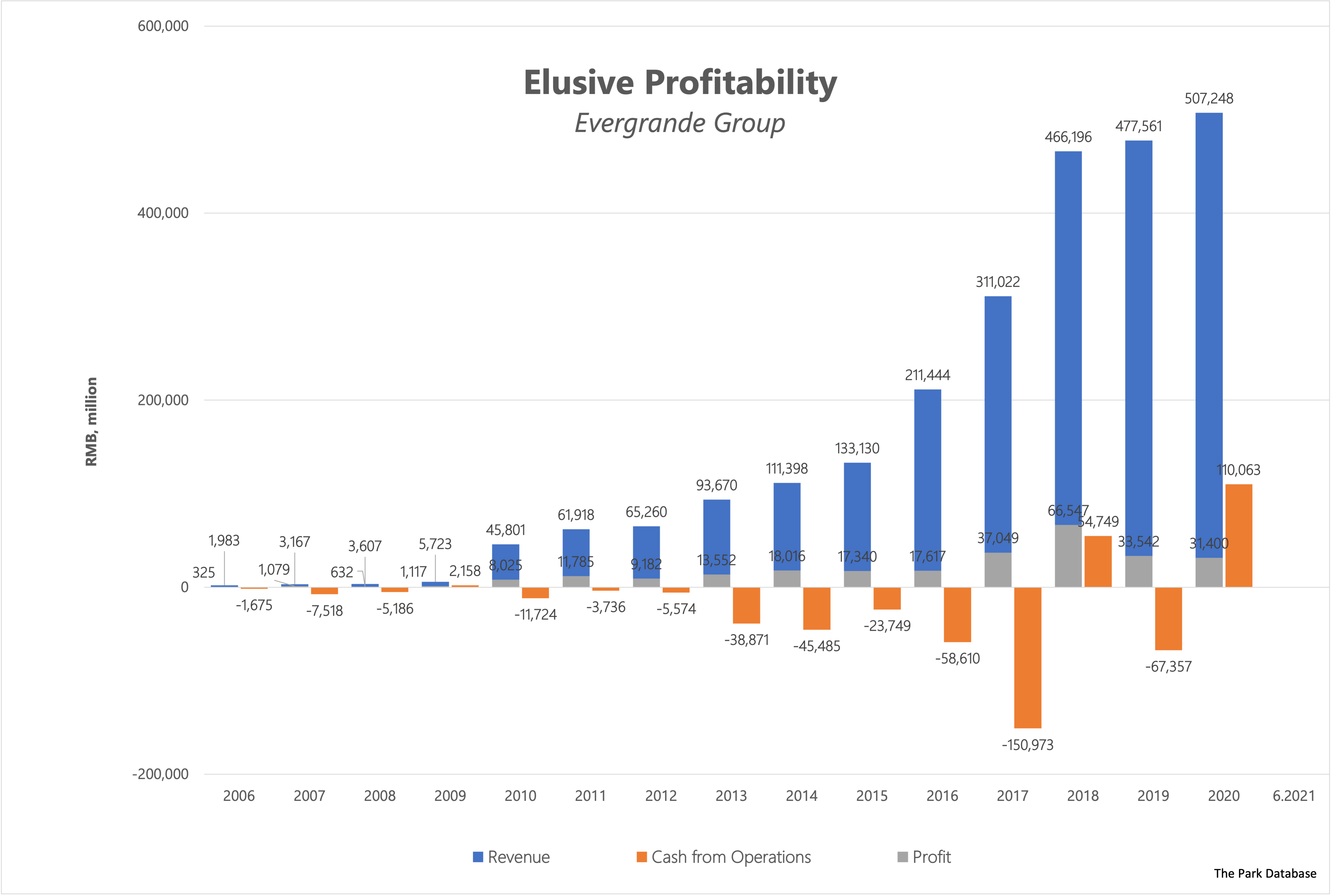

At the time of its IPO in 2009, Evergrande had 20 billion RMB of debt on its books, and sought to raise another 20 billion. This balance grew from 20 billion to over 200 billion within a span of eight years. Even as it grew, however, profitability remained elusive.

Despite throwing ever-growing amounts of cash into development, the company generated only a single year of positive cash flow between 2007 and 2018.

Instead, liabilities ballooned, financing the purchase of ever-growing amounts of land, the development of more than a million square feet of apartments and villas per year, and record revenues – along with record costs. Federal and state taxes ate away at any profits Evergrande was able to generate, so much so that one gets the sense that after a few years, the company was growing desperate.

Its entry into the theme park- and island terraforming-business looks like a hopeful pivot into anything that would help it turn the corner – to say nothing of its expanding diversification into electric automobiles (Evergrande Auto), online streaming (Hengten Networks), online property and automobile marketplace (Fangchebao Group), health food (Evergrande Spring), and healthcare (Evergrande Healthcare).

Again, the problem with theme park development and island terraforming was that Evergrande had never done it before. This was the second major challenge facing Evergrande. Given its inexperience in theme parks and luxury resort islands, what to do?

Evergrande pushed into the theme park industry no-holds-barred. Its team generated designs for Fairyland and Water World that outside designers deemed unbuildable.

Initial designs for the all-weather, all-indoor Fairyland were a series of enclosed pavilions that guests would have to walk between. An inner ring road connected each of the pavilions, enclosed by an 8×8 walkway, and an outer road was traversed by tram. The problem was that the estimated construction costs for these outer shells were equivalent to the cost of all the rides themselves, not to mention that the HVAC requirements for the buildings alone appeared to exceed total projected revenues for the parks.

The first designers who deemed the buildings outrageous or unbuildable were summarily fired; only those that had phrased their reactions in more political, acceptable terms, remained.

For the next few years, Evergrande fumbled their way through the process, signing and firing dozens of designers, as they engaged vendor after vendor to discover the right themes and concepts. Everything they laid their eyes on were plain vanilla, for they wanted mind-blowing and unique – at one point, internal managers suggested Romeo & Juliet as a theme, and challenged the designers to follow suit.

Months of wrangling left Evergrande disenchanted, and instead the team sought to circumvent the outside designers by creating their own Imagineering team. This would consist of 300 ‘creative masters’ hired from all around the world to consult and build out the Fairylands. After marathon sessions of 18-hour teleconference days, this was also deemed an ineffective idea.

In 2018, the central government issued yet another theme park ban. This edict was even more strongly worded, and specifically sought to limit the rampant construction of theme parks with “unclear concepts”, plagued by “blind construction, imitation and plagiarism.” An additional string of mandates sternly rebuked the illegal conversion of natural forests, parks, and green spaces, and the transgression of ecological protections and approval procedures.

Planning for the Fairylands and Water Worlds continued undeterred.

Death Throes

In late 2019, a virus emerged in Wuhan, one that would sweep the globe and shut off economic activity for years. In China, the shutdown was total and catastrophic, at least for the real estate industry, but the party’s leaders used the time as an opportunity to catch up on some housekeeping.

Blanket bans on all sorts of activity were issued, from ones on skyscrapers to ones on “ugly buildings”. Affirming Xi Jinping’s declaration that houses “were for living in”, rather than tools of speculation, the authorities crushed real estate developers by enacting the Three Red Lines policy in 2020, one that limited debt growth with stringent liquidity requirements.

This crushed Evergrande. Like every other Chinese real estate developer, debt growth was the company’s engine. Debt was Evergrande’s primary source of cash, because the company had never been cash flow positive on an operating basis.

With no further debt to finance its projects and growth, the extent of Evergrande’s troubles became clear. It was an end to the confidence game. After its IPO, for nearly a decade, Evergrande had had no trouble raising bonds and funds from investors who believed in the story of its growth and outsize expectations. Forays into theme parks, island building, healthcare, and streaming websites almost seemed to further heighten its glamour and appeal.

But now, the spigot of money had effectively been shut off. Scrambling, Evergrande pressed employees to buy homes and deleveraged where it could. But with no way to finance its operations anymore, the end was inevitable. Evergrande would go into default, de-list from the Hong Kong Exchange, and effectively stop operating altogether, leaving thousands of apartment blocks unfinished, and the fate of its theme parks up in the air.

Late Blooming Flower

The pandemic left the fate of the Fairylands and Water Worlds uncertain; to date, none have been completed.

But whether through luck or dogged determination, Evergrande’s most ambitious development pushed through the pandemic and financial troubles brought on by the Three Red Lines policy, eventually opening in 2021.

By late 2018, the project management for Flower Island had almost been singularly left to a small team of Evergrande specialists and a single outside team, owner’s rep firm Raven Sun Creative.

Five years into the project, the state of Flower Island was representative of a project for a firm seeking to do something that no one in the world had never done before, let alone something it had any remote experience with.

In its ambitions, it was a representation of the age.

Louis Alfieri, president of Raven Sun, helped the small team to analyze, produce, and execute plans that characteristically included spectacular, mind-blowing, and often unbuildable concept designs, across multiple project sites.

The design drawings, which were preliminary at best, included almost no infrastructure for an island that would include a movie studio, three proposed convention centers, 18 spas, 3 theme parks, multiple hotels, botanical garden and arboretum, 8 museums, and a host of other amenities. There was no parking, nor room for enough buses, no train stops, no unloading areas. Fundamentals had to be revisited en masse such as maintenance access, rockwork methodology, fish tank access, animal welfare practices, and guest sightlines for major installations.

For months, experts, consultants, and Evergrande internal teams were in gridlock about the direction of the attractions. Cultural experts argued over the interpretation of Chinese epics, over the minutest of details from the stone texture to how various characters should be represented. Some concepts were deemed to be untouchable, such as time travel themes due to the approaching 100-year anniversary of the CCP.

While the retrofitting, assemblage, and puzzle-like management of the island was proceeding, Chairman Hui decided that the island should host the world’s largest lightshow, with projection maps on every building. This, too, was retrofitted and built into the under-construction island.

Through the collapse of its empire, the unveiling of $300 billion in liabilities, the pandemic, the unraveling of Evergrande’s theme park plans, and millions of dollars in fines for environmental damage done to Hainan’s coastline during construction, this wild and wonderful development continued…developing.

It was like a symbol, a representation, a last gasp of the age, a symbol of the grandeur that Evergrande always aimed for.

In 2021, Flower Island opened with a fairytale theme park, marine animal ocean park, botanical garden, and an audacious waterpark with a 20-story tall mountain, floating pools, and a movie theater on its lake.

These were supplemented by five hotel resorts, one a 5,000-room complex of four European-style castles in ocean, forest, glacier, and desert themes, beachside private villas, and a hot springs hotel with more than 120 characteristic hot spring pools from Japan, Thailand, Italy, Finland, and Turkey.

A Sports and Fitness Center boasted more than 130 “professional sports facilities”, including swimming pools, basketball and tennis courts, archery ranges. Eight modern, monolithic buildings comprised the museum complex, while a 100,000 square meter (11 million sf) international convention hall boasted more than 100 conference halls. Functional areas abounded, including 9 European-style wedding halls, 40,000 square meters of active space for children, adventure, and skateboarding, and a more than 200,000 square meter (2.2 million sf) film and television studio, with over 17 studios, one of which was underwater.

Further amenities included a yacht club, 65-meter sightseeing tower, sightseeing trains, more than 1 million square meters of open gardens, parks, and white sand beaches, a 12-screen luxury cinema, concert hall, a street exclusively made for tea shops, 1,600-seat theater, 150,000 square meter shopping center, a complex of bars, luxury karaoke rooms, and nightclubs, and commercial walking streets.

The audacity was unparalleled. The concept was unprecedented. That it was executed at all was improbable.

The raw energy and ambition of China’s construction boom over the past thirty years was peerless; the largest, most rapid building boom in the history of the world. During these years, hundreds of billions of dollars of development were dreamed up. Some were built, others failed.

Let us appreciate that Flower Island exists as a symbol of that age, of the hope and ambition and raw, zany, wild dreams of the era.