Today’s article has been generously contributed by Yu Shioji, founder of Journal of Amusement Park, an invaluable resource of knowledge on Japanese and other amusement parks around the world.

Table of Contents

Toggle- The Japanese theme park industry entered a boom during the 1960s and 1970s, reaching a peak in the 1990s. Since then, they’ve seen a gradual decline.

- Japan still maintains a ratio of theme parks and theme park attendance that is high relative to its population, on par with that of the United States.

- However, Japan has historically lacked the ecosystem and talent pool for large-scale ride technology and manufacturing, which are mostly in the United States.

- With the revitalization of Universal Studios Japan, the former managers of that park and Oriental Land Company have effectively acted a diaspora of talent, taking their abilities to revitalize parks around the country.

- Their efforts have mostly focused on low-tech immersive attractions, such as events, theming, exhibits, and expanding the visitation base to non-traditional theme park visitors. These efforts have been expanded to some of the most notable parks nationwide, including Huis Ten Bosch, Seibuen, Yomiuriland, and Miroku-no-Sato.

The Rise and Decline of Japan’s Theme Park Golden Age

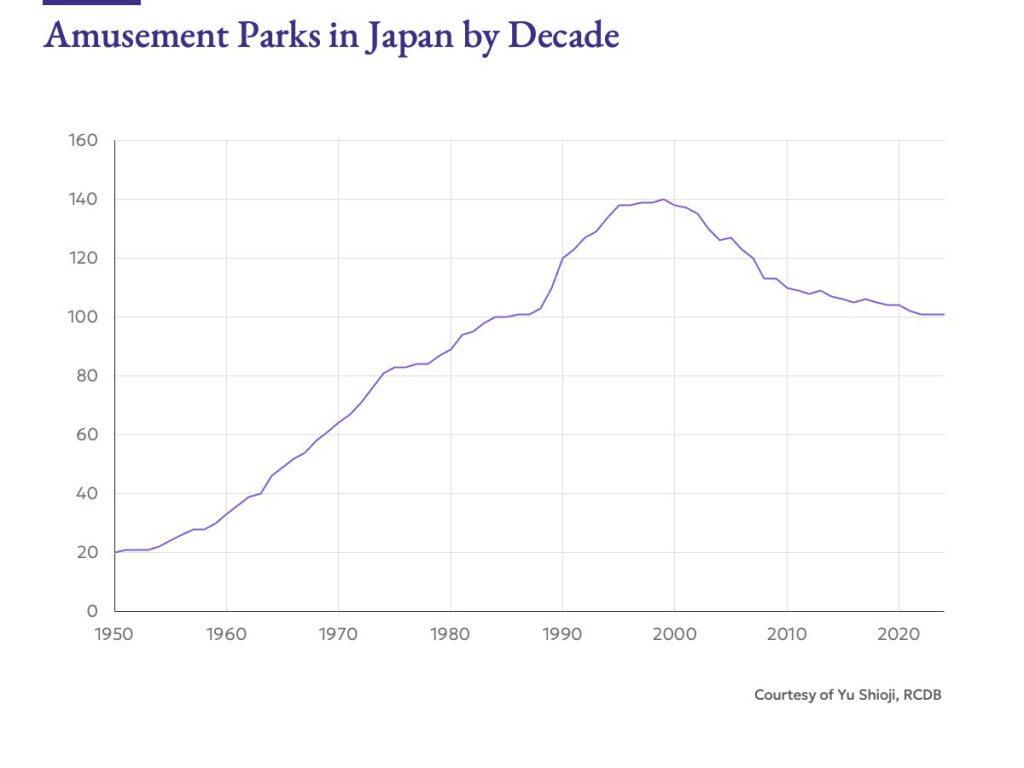

Japanese amusement parks have been in consistent decline since the mid-1990s due to a lack of new developments. However, since the 2010s, this decline has slowed somewhat, and a new trend has emerged in the 2020s.

Japan faces numerous challenges, including a declining birthrate, an aging population, and a significant national debt. Understanding the factors behind the recent change in the pace of amusement park decline could offer valuable insights for parks outside Japan, which may encounter similar challenges in the future.

In this discussion, we will review historical trends related to amusement park revitalization—one of the key factors contributing to the slowdown in decline—and provide an overview of emerging trends in the 2020s.

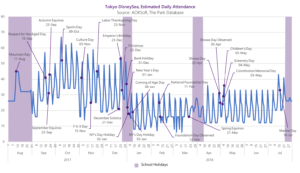

The graph below shows the number of Japanese amusement parks over time. Each park included in the count had at least one roller coaster and at least four additional non-coaster rides during the same period.

Many Japanese amusement parks were built in the 1960s and early 1970s, a time when Japan was experiencing rapid economic growth following the Second World War. These parks were often classic amusement parks, but some, such as Takarazuka Family Land (1911–2011, with major updates in 1960 and 1967), Yokohama Dreamland (1964–2002), and Nara Dreamland (1961–2006), were influenced by Disneyland, which opened in Anaheim in 1955.

Many Japanese amusement parks were built in the 1960s and early 1970s, a time when Japan was experiencing rapid economic growth following the Second World War. These parks were often classic amusement parks, but some, such as Takarazuka Family Land (1911–2011, with major updates in 1960 and 1967), Yokohama Dreamland (1964–2002), and Nara Dreamland (1961–2006), were influenced by Disneyland, which opened in Anaheim in 1955.

Following a temporary period of stagnation, the number of amusement parks grew rapidly from the late 1980s through the 1990s. This growth was largely driven by public-private joint investments known as “third-sector” projects. These developments were supported by the Resort Law, which provided tax incentives and financial assistance for resort-area development. Since the opening of Tokyo Disneyland in 1983, many new parks either emulated elements of Tokyo Disneyland or deliberately adopted a different approach.

In the 1990s, Japan entered a recession that has persisted into the 2020s, placing many amusement parks in a difficult financial position. During this period, several parks closed without implementing clear recovery strategies, while others attempted revitalization efforts.

Revitalization often involved a change in park operators. For example, Kamori Kanko, which manages Rusutsu Resort, took over operations for Himeji Central Park, Space World, and Noboribetsu Marine Park Nix, all of which were initially run by different companies.

At the time, Kamori Kanko was in a phase of rapid expansion, and their revitalization strategy primarily focused on cost-cutting. This approach proved insufficient for some parks, such as Space World, which ultimately closed in 2018 due to a lack of effective measures to boost its appeal.

Other parks, such as Huis Ten Bosch and Lagunasia, were operated by the travel agency H.I.S. The company aimed to cut costs and leverage synergies with its core business by offering travel packages. While these efforts achieved moderate success, the COVID-19 pandemic led to significant financial difficulties, resulting in the sale of Huis Ten Bosch.

Overall, the revival of Japanese amusement parks has faced numerous challenges. Despite some turnover, where older parks closed and new theme parks opened, the overarching trend since 2000 has been a steady decline in the number of amusement parks.

Japan Matches the U.S. in Theme Park Density

A defining characteristic of the Japanese amusement park market is the high proportion of major theme parks.

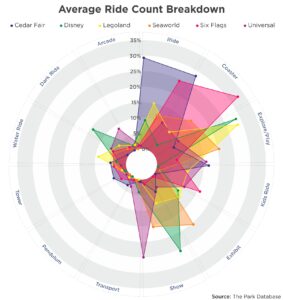

Japan has three theme parks with annual attendance exceeding 10 million: Tokyo Disneyland, Tokyo DisneySea, and Universal Studios Japan, to its 43 amusement parks with two or more roller coasters, according to the Roller Coaster Database. This is a ratio of 3 major parks out of 43, or 7.0%, and is equivalent to 0.25 major parks per 10 million people.

In the United States, the number of theme parks with attendance over 10 million varies year to year but typically ranges between 7 and 8. Counting all Disney and Universal affiliates brings the total to 9. Given that there are 120 amusement parks with two or more roller coasters in the U.S., this leads to a ratio of 9 major parks out of 120, or 7.5%, equivalent to 0.27 parks per 10 million people.

In other words, Japan’s large-scale theme parks are comparable in scale to those in the United States. These two countries are unique in maintaining this ratio of major theme parks.

Japan’s Struggle with Ride Tech and Talent Gaps

Despite having world-class theme parks, Japan traditionally lacked a large talent pool for attraction development, as most design and development work was done in the United States.

Notably, Tokyo Disney Resort is the only Disney park not operated by Disney itself; it is managed by Oriental Land Co., Ltd. This arrangement has allowed Oriental Land to cultivate expertise in marketing and operations, modernizing practices within Japan’s theme and amusement parks.

This dynamic shifted significantly around 2018. Universal Studios Japan (USJ), established through public-private investment, including support from Osaka City, faced declining visitor numbers after its opening. In 2005, Goldman Sachs intervened to stabilize the park, and by 2011, USJ achieved a remarkable turnaround under the leadership of Takeshi Morioka, who came from Procter & Gamble (P&G). Morioka chronicled this period in three books published in 2014 and 2016:

- Why the Rollercoaster in USJ Runs Backward? (ISBN: 978-4041041925)

- The Single Way of Thinking That Dramatically Changed USJ (ISBN: 978-4041041413)

- Probability Strategy for Marketing (ISBN: 978-4041041420)

After his books gained attention, Morioka left USJ to found Katana Co., Ltd., a marketing consulting firm supporting industries beyond theme parks. Katana began working with Nesta Resort Kobe in 2018 and later supported Seibuen Amusement Park, Huis Ten Bosch, and Immersive Fort Tokyo. Morioka’s colleagues also branched out, consulting for various amusement parks.

For additional context, Daisuke Suzuki has detailed the story of Goldman Sachs’ turnaround of USJ.

Talent Trailblazers: Former USJ and Disney Leaders Spark a Revival

Katana’s approach to attraction development was honed at Universal Studios Japan (USJ). However, USJ does not offer expertise in creating ride attractions, except for motion simulators. Instead, the primary know-how available in Japan revolves around attractions that rely on human performances, such as Halloween events and live shows.

As a result, many of Katana’s attractions are motion simulators or experiences that depend heavily on human resources.

Immersion Over Innovation: Low-Tech Magic

Nesta Resort Kobe

One distinctive example of Katana’s work is Nesta Resort Kobe. Originally operated by the Pension Welfare Service Public Corporation, it was primarily a lodging facility. Katana transformed it into a day-trip destination by introducing activities like ziplining and barbecuing, achieving a turnaround with minimal investment.

Seibuen Amusement Park

Katana’s next major project was the revitalization of Seibuen Amusement Park. The centerpiece attraction was a flying theater by Brogent, featuring Japanese intellectual property like Godzilla. The park was themed around the Showa 30s (late 1950s to early 1960s), evoking the nostalgia of Japan’s high-growth era. A recreated shopping street featured cast members portraying residents who performed atmospheric shows. This marked the first direct deployment of USJ-style immersive techniques by former USJ personnel.

Seibuen Shopping Street. Courtesy of Yu Shioji

Seibuen Shopping Street. Courtesy of Yu Shioji

Seibuen’s restaurant was also remodeled to resemble a railway dining car. The sound of a moving train and projected window visuals enhanced the immersive experience, while the menu reflected the dining car theme. The restaurant even hosted an immersive theater experience. An attempt to introduce a park-specific currency to boost spending was later abandoned due to convenience issues.

Courtesy of Yu Shioji

Huis Ten Bosch

Huis Ten Bosch similarly adopted immersive experiences, hosting Halloween horror events akin to USJ’s Halloween Horror Nights. They also introduced a new simulation ride. While the park originally had a Dutch theme, its scope has expanded to “Europe” to attract a broader audience. A new Miffy-themed area was also added to appeal to families.

Immersive Fort Tokyo

In the United States, standalone Halloween horror attractions inspired by Universal Studios are set to open in Las Vegas. However, Japan has already seen the launch of such a facility with Katana’s Immersive Fort Tokyo in 2024.

This temporary park, located in a repurposed shopping mall, features multiple immersive theaters—a first in the world, according to Katana. The park offers two immersive theaters, escape-room-style puzzles, a horror maze, horror games, video-based walk-through attractions, and atmospheric performances by cast members, a technique first deployed at Seibuen. Despite its high-quality content, the park has struggled to attract visitors due to the unfamiliarity of the term “immersive” in Japan and the absence of ride attractions typically expected in a “theme park”.

Junglia

Looking ahead, Katana plans to open JUNGLIA in Okinawa in 2025. This resort-style theme park will highlight Okinawa’s natural beauty and is strategically located near the Churaumi Aquarium, which draws about 3.5 million visitors annually. High annual attendance and spending are anticipated.

Others

Thanks to Katana’s influence, labor-intensive immersive attractions are becoming more popular in Japanese amusement parks, especially around Halloween. Nagashima Spa Land, known for having the most roller coasters in Japan, hosts Nagashima Zombie Island, where zombies roam the park grounds. Fuji-Q Highland, home to the Guinness World Record-holding “Labyrinth of Fear,” offers a long outdoor horror maze on select days. Sanrio Puroland has also hosted immersive theater events featuring well-known comedians.

Labyrinth of Fear. Source

Labyrinth of Fear. Source

This trend indicates a growing integration of immersive theater-style attractions into Japanese amusement parks, compensating for the country’s lack of advanced ride systems and technological ecosystems.

Expanding the Visitor Base

Another major transformation introduced by Katana is in the area of marketing. Katana’s representative, Takeshi Morioka, is a data-driven marketing expert who previously led marketing efforts for P&G in the United States. In his book, Morioka emphasizes that successful marketing hinges on increasing “M”—the probability of purchases per person within a given market. To achieve this, he advocates focusing on expanding the number of unique purchasers rather than increasing repeat purchases from the same customers.

At Universal Studios Japan (USJ), this strategy was implemented by broadening the park’s concept from a strictly movie-themed park to a high-quality entertainment park. USJ also expanded its target demographic by introducing family-friendly attractions and incorporating popular Japanese intellectual properties (IPs) such as Monster Hunter and Biohazard. Similarly, Huis Ten Bosch, known for its meticulous recreation of Dutch streets, is expanding its theme to encompass all of Europe and introducing a Miffy-themed family area to attract a wider audience.

This approach of adopting broader themes to avoid overly niche targeting is not unique to Japan. Family-friendly roller coasters are popular worldwide, but this strategy has notably influenced Japanese amusement parks. For instance, Fuji-Q Highland, once known for its massive, world-renowned thrill rides, shifted its strategy in 2023 by introducing ZOKKON, a family launch coaster by Intamin. Additionally, Fuji-Q Highland implemented a face recognition system in 2018, enabling the collection of personal data to trace individual guest actions. Yomiuriland has also diversified its offerings by adding attractions like a botanical garden to appeal to audiences beyond traditional amusement park visitors.

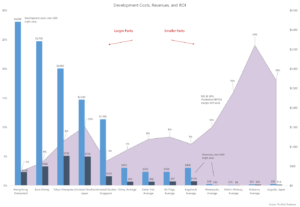

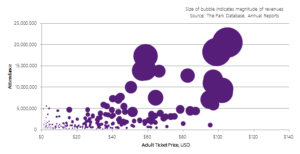

Perhaps the most significant achievement by Morioka and USJ in the amusement park industry was normalizing higher ticket prices. During USJ’s turnaround, ticket prices were raised by 31%. Inspired by USJ’s success, Tokyo Disney Resort followed suit. Between 2001 and 2011, ticket prices at Tokyo Disney Resort rose by less than 20%, but from 2011 to 2021, prices increased by 40%. Additionally, between 2021 and the present, peak-period ticket prices have risen by another 25%.

In Japan, which still struggles with deflation, the theme park industry stands out as one of the few sectors to implement such significant price hikes without altering the core services. Encouraged by the continued strong performance of USJ and Tokyo Disney Resort, other amusement parks across Japan have also raised their prices. These price increases have helped offset rising energy and labor costs, especially in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic. Importantly, because these price hikes were implemented before costs surged, many amusement parks were able to mitigate financial challenges effectively.

Miroku-no-Sato

There are few documented cases of amusement park revitalization that credit specific individuals, but one notable example is Miroku-no-Sato in Hiroshima Prefecture. Mr. Shimizu Gun, who previously oversaw attraction maintenance and safety management at Oriental Land Company and Universal Studios Japan, was appointed as the park’s representative director and vice president. Since his appointment, he has implemented various improvements (https://blog.mirokunosato.com).

Miroku-no-Sato, operated by Tsuneishi, a local shipping company, is known for its attraction “Itsuka Kita Michi” (“Road We Came Once Upon a Time”), which vividly recreates 1950s scenery within the park’s expansive grounds. The revitalization here has been modest and practical, focusing on eliminating negative perceptions. Efforts included renovating nursing rooms, introducing cashless payment options, and revising the staff dress code to improve customer service.

Yomiuriland

Another well-known example of amusement park revitalization in Japan is Yomiuriland. Owned by the Yomiuri Group, which operates major newspapers, television stations, and public gambling facilities, the park has a strong corporate foundation. However, attendance once plummeted to around 600,000 visitors annually—about half the number of other Tokyo-area parks of similar size.

The turning point came with the introduction of winter illuminations. In 2010, Yomiuriland launched “Jewel Illumination,” the first large-scale illumination event of its kind in Japan. The dazzling electric lights, which took full advantage of the park’s vast size and hilly terrain, were well received. Attendance steadily increased, reaching 1.4 million visitors per year by 2014.

In 2015, Yomiuriland further boosted its appeal by opening the Goodjoba! area, a themed zone featuring attractions tied to products from various Japanese companies. More than 10 new attractions were launched simultaneously. While primarily aimed at children, Goodjoba! was thoughtfully designed to engage adults interested in the showcased products, offering the added benefit of securing sponsorship deals. This move drove annual attendance to nearly 2 million. The Goodjoba area expanded further in 2021.

Yomiuriland has continued to diversify its offerings to attract a broader demographic. A natural hot spring bathing facility was added, targeting older visitors, and a botanical garden was introduced to appeal to women who prefer gentler experiences over intense rides. Future plans include adding aquariums to further enhance the park’s appeal. These strategic additions aim to significantly expand Yomiuriland’s customer base beyond traditional amusement park visitors.

The Revitalization Challenge

As we have seen, Japanese amusement parks risk falling into decline if they remain trapped within the traditional concepts and themes established during their founding. To avoid this fate, it has become essential to adopt strategies that broaden both the target audience and customer base. These strategies should be low-cost and adaptable, relying on human resources or inexpensive elements to generate capital for future investments.

While such approaches are already common in other countries, understanding the unique challenges faced by Japan’s amusement parks offers valuable insights. This article serves as a starting point for examining these challenges, exploring the successes and failures of parks that have attempted revitalization, and developing strategies to help amusement parks in other countries avoid a similar decline.