Table of Contents

At their peak in the 19th century, world’s fairs were unparalleled spectacles of industry, commerce, and entertainment, unique in their ability to draw visitors and leave behind significant cultural impact and influences on the collective imagination.

More simply, the fairs of that era were the greatest LBE attractions of all time. In modern terms, some of these events were like a combination of a Consumer Electronics Show, Canton Fair, Apple Macworld Keynote, Disneyland, TED Talk, Universal Citywalk, MoMA, factory tour, cultural village, and scientific convention. Artifacts of the First Age of Globalization, their overarching goal was to exhibit all aspects of human commerce, knowledge, and endeavor in a single place, and their scale, volume of visitation, and lasting influence was awe-inspiring.

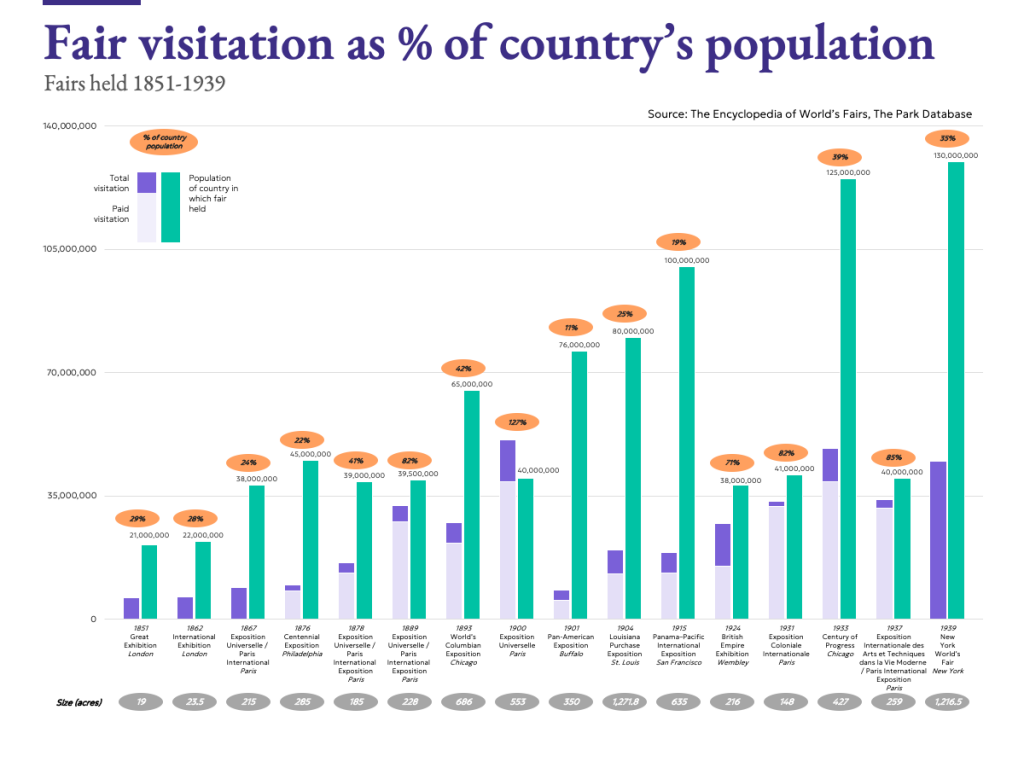

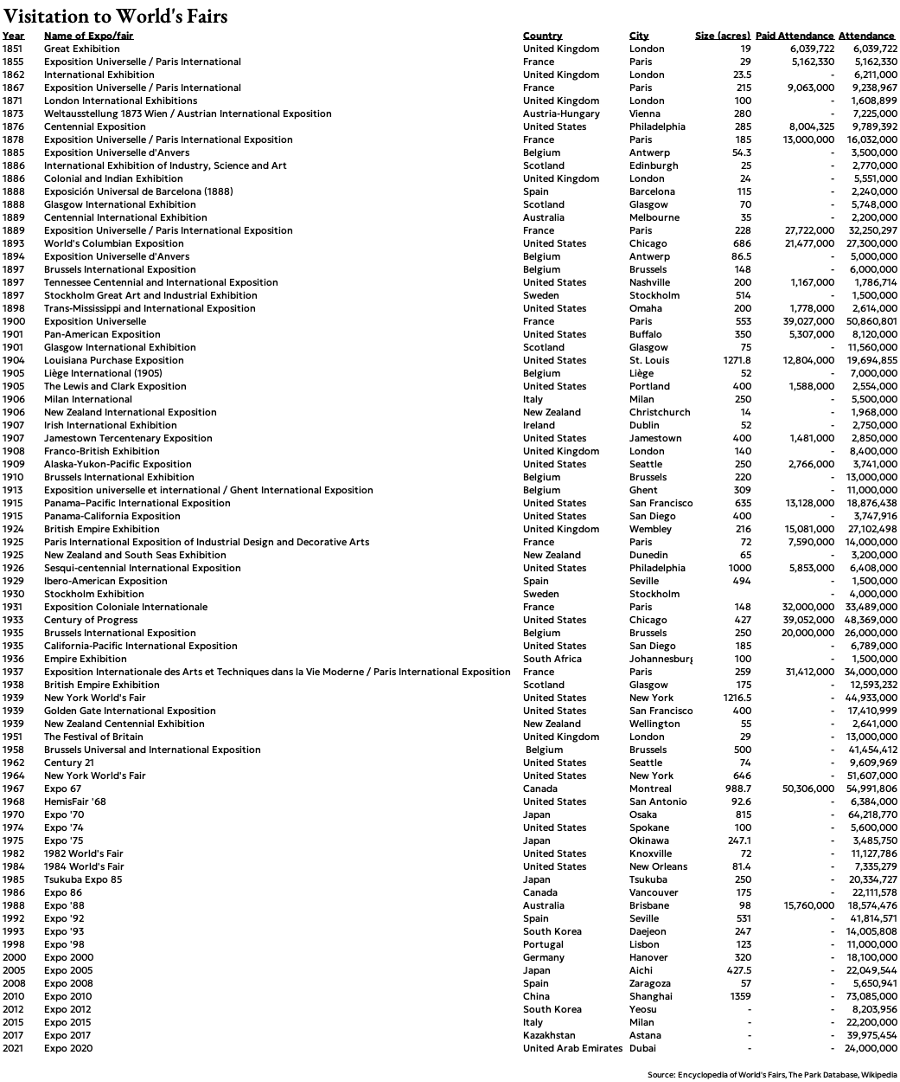

World’s Fairs continue today. The latest, the 2020 Dubai Expo (which took place in 2021-2022 post-pandemic) boasted 24 million visitors to a country of 10 million. But like most of the world’s fairs of the past fifty years, raw visitation numbers have been high (some suspiciously so) without the same degree of worldwide cultural and societal impact. Modern fairs also benefit significantly from a large pool of available tourists (Dubai hosted 14 million overnight tourists in 2022), which was not available to 19th century cities in an age of steamships and rail. More on this later.

Over the 20th century, many economic and geopolitical factors caused world’s fairs to evolve away from their role as singular sources of spectacle, innovation, and entertainment to the role they hold today, in which they function sort of as an exchange of goodwill among nations.

In this post I want to celebrate what were once the most mind-blowing spectacles that ever existed. I’ll lead with some of the mind-blowing characteristics of World’s Fairs (how big they were, what they were in the first place), then present what seem to be the likely reasons behind their fading significance.

A Phenomenal Draw in the Age of Steam

In their heyday, world’s fairs were the singular destination for nearly all tourism. This sounds like an exaggeration, but it’s not.

The visitation they drew was unrivaled, even in the modern era. In fact, adjusting for modernity makes their visitation even more impressive.

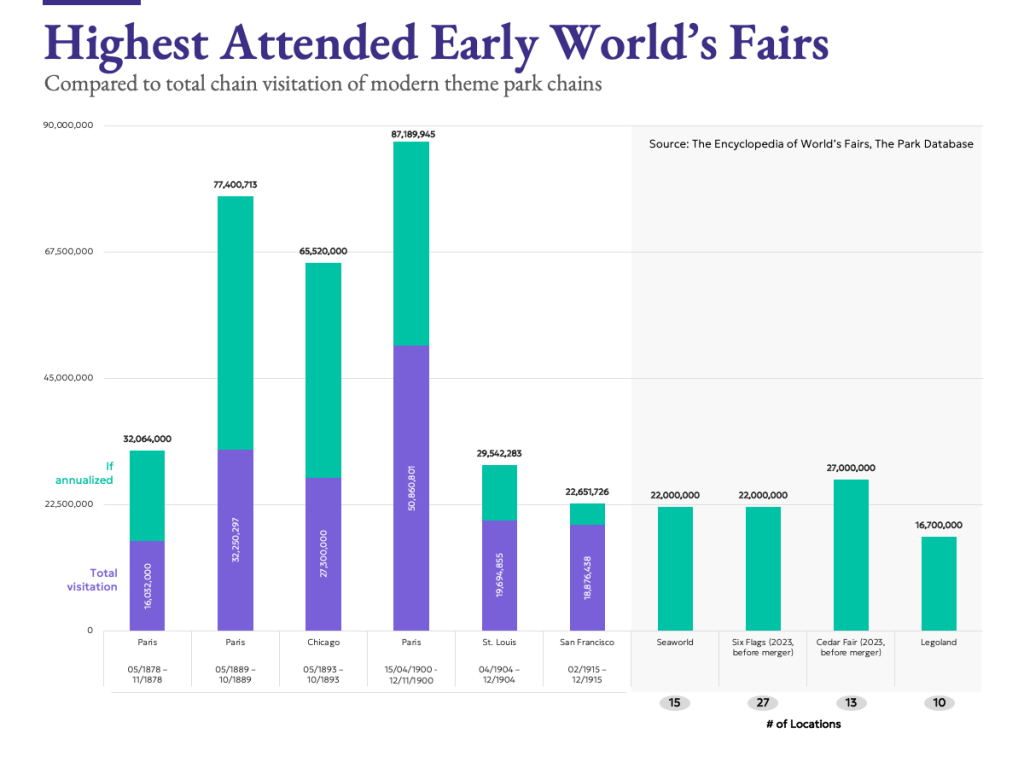

The Chicago World’s Fair (World’s Columbian Exposition) in 1893 drew 27 million visitors (21.5m paid) in a six-month period between May and October. This was 40% of the population of the United States at the time. Compare this to the 22 million visitors to Seaworld’s combined 15 parks, or Six Flags’ 27 locations, in 2023.

This exercise can be repeated with nearly every major fair during the late 19th century and early 20th. The Exposition Universelle, the 1900 fair held in Paris, experienced even greater volumes – 39 million paid visitors of a total 51 million – in the seven months between April and November. This was a figure exceeding the population of France at the time. Compare this to the 16 million visitors to Disney Paris’ two theme parks over a twelve-month period in 2023.

The logistics required to accommodate such a large number of visitors was staggering. Single day visitation at the Philadelphia (1876) and 1889 Paris Expositions was 257,590 and 397,150, respectively. Chicago on October 9th, 1893, recorded 716,881 paid visitors, which by at least one account was the single highest attended event in American history (excluding free-of-charge parades and processions). For such a crowd, a single concession prepared “eatables sufficient to allay the wants of 300,000 persons…this company had eight restaurants and forty lunch counters in operation…with 40,000 pounds of meat, 12,000 loaves of bread, 200,000 ham sandwiches, 400,000 cups of coffee, 15,000 gallons of cream, and pies and cakes by the wagon.”

Such figures, which are nearly 10x the peak-day crowd size of comparable Disney and Universal Studios theme parks today, and multiples of the record attendance at 2024’s State Fair of Texas, are almost hard to comprehend.

History of the World’s Fair (1893), E.B. Treat, Publisher

History of the World’s Fair (1893), E.B. Treat, Publisher

Disney theme parks are the point of comparison here because they’re the world’s highest-attended theme parks and paid attractions, but what makes the drawing power of world’s fairs even more impressive was the state of mass tourism during the late 18th century. That is, there was no mass ‘tourism‘. In that pre-automobile, pre-airplane society, local visitors had to arrive via horse-drawn carriage or trolley, while far-flung visitors journeyed for day or weeks via steamship and rail.

These days we take for granted that a given metropolitan market has a built-in base of tourists. Both intra- and inter-regional travel is typically measured in the millions, in volumes that dwarf their resident populations. I.e., France is visited by more than 100 million tourists. Orlando hosts more than 70 million, New York more than 60 million. Thailand, Las Vegas, Los Angeles, draw 40+ million visitors a year. There are myriad factors that made this possible over the past century – the development of the passenger airline and automobile industries, new sources of energy production and its consumption, widespread affluence and an increase in leisure time, and so on.

But in the early 20th century, such travel and tourism beyond the bounds of one’s local area was an upper-class endeavor. In the United States, “30,000 to 60,000 tourists” visited Southern California annually in the years 1901-1903, a fact that still earned the designation of Los Angeles as “essentially a tourist town.” Niagara Falls hosted up to half a million visitors in the 1890s, the Jersey shore attracted 150,000 annually, while Yellowstone National Park drew “nearly 7,000 a year”.

In this milieu, to have an attraction like the Chicago World’s Fair (in 1893) draw more than 27 million visitors meant there was no established tourism infrastructure or volumes to draw from. The equivalent of $4 billion dollars was spent over a period of two years to construct an entirely new city. With a lack of hotel rooms, residents converted their homes into temporary barracks for friends and visitors.

These world’s fairs were superlative in every aspect. Average fairground sizes for World’s Fairs have been in the range of 200+ acres, more than twice the size of an average Disney or Universal Studios park. The largest fairgrounds in the United States, in Texas and Minnesota, range from 270 to 320 acres in size. Compare this to the Chicago’s World Fair (1893), set on fairgrounds of nearly 700 acres, while the St. Louis World’s Fair (1904) and New York World’s Fair both took place on over 1,200 acres, records that wouldn’t be broken until Expo 2010 in Shanghai, whose grounds were 1,360 acres in size.

An Artifact of the Industrial Age

Hopefully, now that I’ve impressed on you the awe-inspiring scale of these fairs, you might be wondering just what all these people came to see?

The clue is in the early names themselves – e.g., The Great Exhibition of the Works of Industry of All Nations (1851, London), The Great Industrial Exhibition (1853, Dublin), Exhibition of the Industry of All Nations (1853, New York), or the International Exhibition of Arts and Manufactures (1865, Dublin). World’s Fairs grew out of the trade fairs that had been organized in France and the United Kingdom for centuries. These were expositions in which manufacturers and artisans exhibited their pieces, vied for awards, and sold their wares.

The official “Illustrated Catalogue” for London’s Great Exhibition of 1851, which was credited with being the first “world’s” fair for both its reach (with visitation equivalent to 30% of the United Kingdom’s population at the time), and for the architectural and engineering marvel that was its exhibition grounds (the Crystal Palace, in Hyde Park), is several hundred pages of wide-ranging goods: decorative furniture, wood carvings, jewelry and gemstones, carriages, ornamental weapons, furniture, chandeliers, glassware, engines, beehives.

Official descriptive and illustrated catalogue, v1., 1851

Official descriptive and illustrated catalogue, v1., 1851

As the industrial age progressed, the exhibits were accordingly upgraded. Paris’ 1889 Exposition Universelle featured a Galerie des machines, the largest vaulted building built up to that time, under which visitors on moving bridges could view 20 acres of gathered engines, dynamos, and transformers.

Similarly, Chicago’s 1893 fair featured a Palace of Mechanic Arts, in which the engines and dynamos gathered represented more than 24 million horsepower, enough to designate it as the largest power plant in the world, but with a functional purpose. Not only did the dynamos charge the electric transports and power the 5,000 arc lights and 120,000 incandescents at the fair, the machines on display crafted things for visitors, from gold bead necklaces to watch chains, to looms and printing presses.

Galerie des machines, 1889. Source: Wikipedia.

Galerie des machines, 1889. Source: Wikipedia.

In that era when economies were based primarily on agricultural and industrial “stuff”, the spectacle of seeing innovative, novel goods and products from every corner of the world alone could attract millions of visitors. With agriculture and industry accounting for 75 to 90% of the 19th century economy, such shows were a triumph, a celebration, an all-encompassing display of the entire world’s economy in a single place.

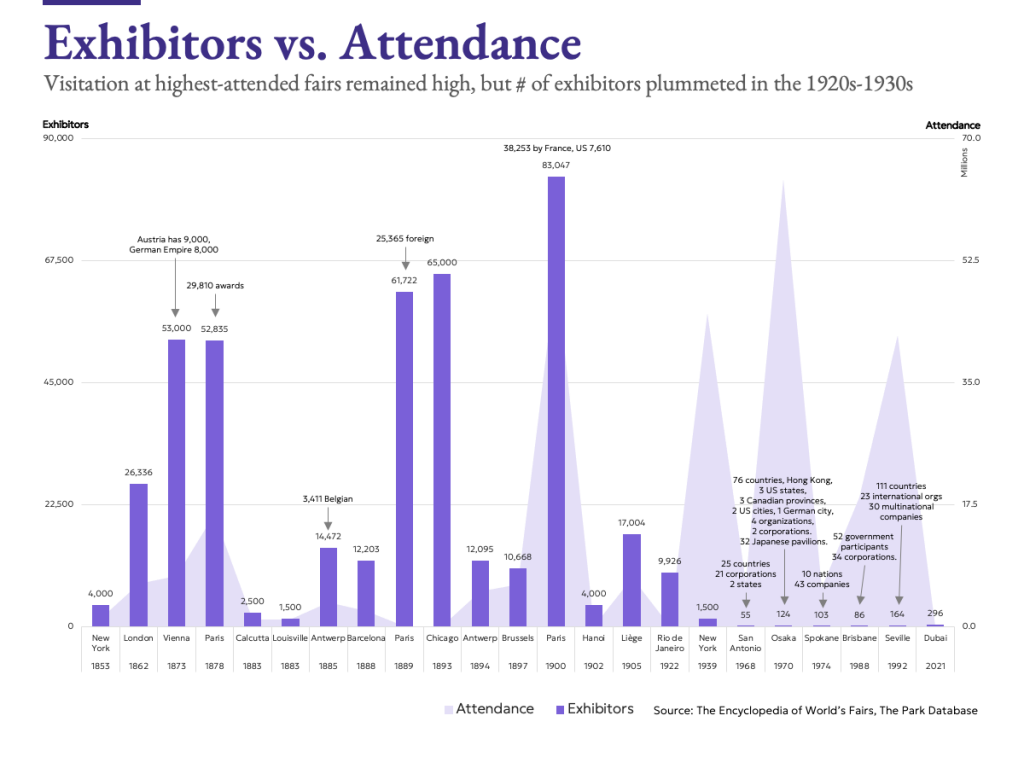

The 1862 International Exhibition in London hosted 26,000 exhibitors, a record that would be broken with every successive major fair, with 53,000 in Vienna in 1873, and in Paris, 62,000 in 1889, and over 80,000 in 1900. For a sense of scale and comparison, the modern world’s largest trade show is the Canton Fair in Guangzhou, which annually hosts approximately 25,000 exhibitors.

Evolution of the Midway

While the first fairs started with these commercial aims, by the late 19th century, the emphasis had shifted to that of all-encompassing spectacle. Fair organizers realized that while exhibitor fees, from both private entities and governments, constituted a significant portion of revenues, what would make or break the financial fortunes of the event were the crowds.

Viennas’ 1873 exhibition marked a shift from industry, progress, and commerce to entertainment. Organizers had realized that people “wanted to travel the world in one day”. Organizers of the Melbourne exhibition in 1888 quickly added sideshows and rides, from electric railway and shooting gallery, to Swiss singers and yodellers, organ recitals, bicycle rides, and acrobatic feats, when attendance began to decline. By 1889, critics complained that “it was all too much fun, claiming that the public sought only amusement and neglected to learn from the exhibits.”

Melbourne Exhibition, 1888. Source

Melbourne Exhibition, 1888. Source

In 1893, the Chicago World’s Fair included, in addition to the exhibits of manufacturing, industry, agriculture, and mining, gondola rides, electric boats, a garden island, and the world’s first Ferris wheel anchoring one end of a midway crowded with performers and touts from Egypt, West Africa, Japan, Southeast Asia, and the Middle East, in buildings crafted skillfully to resemble a Japanese temple, old Cairo, a Turkish village, and an exact reproduction of the Blarney Castle. The foreigners hosted cafes and restaurants, performed native dances, and sold souvenirs. To lend a degree of seriousness, the fair also exhibited classical and modern art, and hosted scientific and philosophical conventions.

The midway, or boardwalk, became an established element at all subsequent fairs. Buffalo’s World Fair of 1901, besides being remembered as the event in which President McKinley was assassinated, featured a midway with ethnic villages, a carousel, ostrich farm, scenic railroad, and attractions with such evocative names as a Trip to the Moon, Dreamland, House-Upside-Down, and Darkness and Dawn. Attractions became bolder and more experimental, culminating in the 1930s at fairs in New York, Chicago, and San Francisco, which featured nudist colonies, topless performers posing in “living magazine covers”, and all manner of striptease and burlesque shows.

Source

Source

Enduring Impacts

But while such concessionaires might have monopolized the attention (with some arrested), the underlying sentiment shines through. From the beginning, the premise of these World’s Fairs were to showcase the extent of human endeavors and accomplishment, technology, and innovation. Many were organized around the themes of universality, human “greatness” and progress.

Accordingly, much of the architecture, crafts, and inventions first displayed or developed specifically for these fairs made lasting, landmark contributions to the world’s cultural heritage. Typewriters, mechanical calculators, telephones, and phonographs were first displayed at the 1876 Centennial Exposition (1876). French impressionist art and the British Arts & Crafts movement were first showcased at the 1883 American Exhibition of the Products, Arts and Manufacturers of Foreign Nations (Boston), the Ferris Wheel was introduced at the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition, and refreshments like hot dogs, ice cream cones, and ice tea made their debut at the 1904 St. Louis Fair, alongside baby incubators. Ideas such as functionalism/Swedish Modern design trace their origin to the 1930 Stockholm Exhibition, while interest in Spanish colonial architecture is attributed to the 1915 Panama-California Exposition (San Diego).

Fairs also contributed lasting impacts to our physical world. France gifted the torch of the yet-unfinished Statue of Liberty to the United States for the 1876 exhibition, while the Eiffel Tower was built for the 1889 Exposition Universelle. The Paris Metro and the Grand Palais were built for the exposition in Paris just a decade later. Wembley Stadium was originally constructed for the 1924 British Empire Exhibition, Atomium hailed the arrival of the nuclear age in Brussels in 1958, while Seattle’s Space Needle was built for the Century 21 exposition in 1962. Other tourist attractions and theme parks, such as Montreal’s La Ronde (1967), San Antonio’s Tower of the Americas (1968), and Seville’s La Isla Magica (1992), owe their existence to their respective fairs. So too for Disneyland’s It’s a Small World ride, which was initially an exhibit at the 1964 New York fair.

Crumbling Foundations

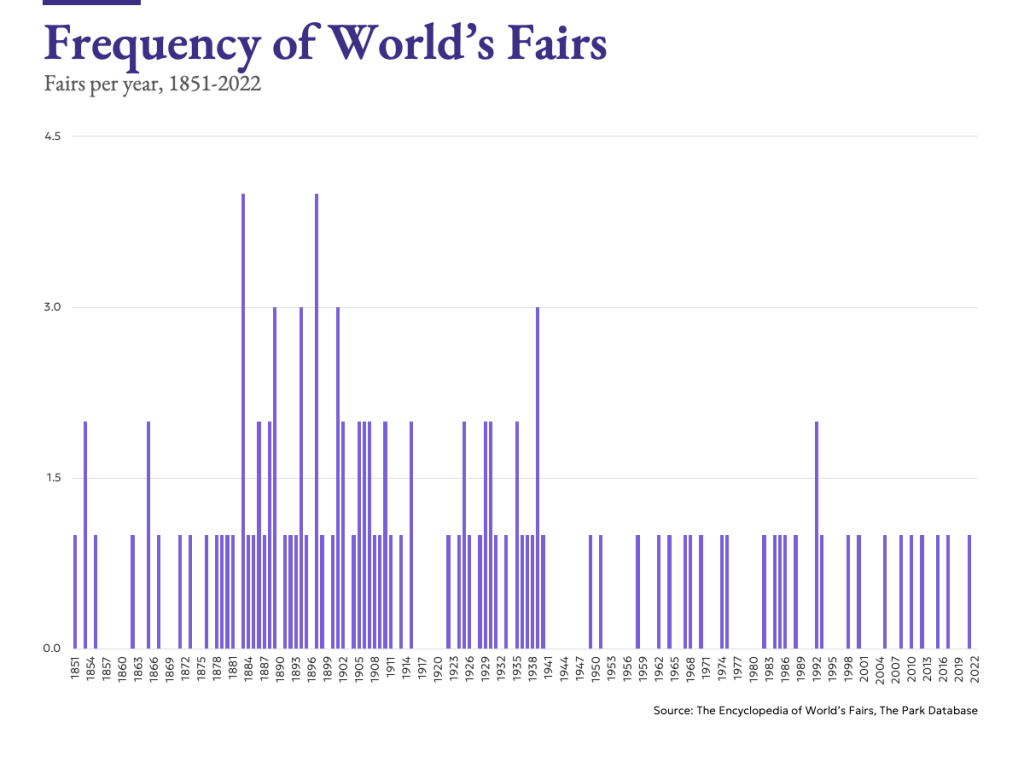

But as the world entered the 20th century, the emphasis and importance of world’s fairs began to decline. From a peak of two, or sometimes four fairs per year in the late 19th century, fairs have happened approximately two to four times per decade for the past half century.

The 20th century was tumultuous for an attraction whose premise was based on global trade and harmonious relations, with world and regional wars, to a depression, to the Cold War. There were only two fairs in the decade between 1941 and 1951, and only one between 1950 and 1960.

The 20th century was tumultuous for an attraction whose premise was based on global trade and harmonious relations, with world and regional wars, to a depression, to the Cold War. There were only two fairs in the decade between 1941 and 1951, and only one between 1950 and 1960.

Decline in Exhibitors

But the warning signs could be seen even in the decade previous to that. Recall that over 80,000 exhibitors were present in the 1900 Exposition Universelle. At the New York World’s Fair, there were only 1,500. This was even with a visitation (45 million) nearly equivalent to that of the former (51 million).

Exhibitors were not only the pillar upon which these world’s fairs were founded, they were one of the primary attractions for visitors, as well as one of the major sources of revenue (in the form of exhibition fees), with fees paid by governments and individual companies alike amounting to millions of dollars in today’s terms. A collapse in the number of exhibitors meant a collapse in both the attractiveness and economic fortunes for the fairs.

As early as the 1860s, competition in the form of journals, specialized trade fairs, and “congresses” had emerged to dilute the impact of such expositions for the dissemination and promotion of technical and cultural progress. Simultaneously, exhibitors became increasingly dissatisfied. As exhibitions became more spectacular, manufacturers found themselves having to “develop specially created products. For the decorative arts and commodities, it had become customary to exhibit spectacular objects” that proved hard to sell. They further complained of fair logistics, which often left them in uncertainty about the dimensions of the space they would be allocated, which often turned out to be too small.

While incurring high expenses for travel and transport, exhibitors discovered there was little immediate commercial benefit to exhibiting. For the purposes of “doing business involving meeting new retailers, dealers, and contractors, specialized trade fairs were much more effective and much less costly.”

Despite such trends in the 1870s, the number of exhibitors still continued to rise for the next quarter century, until hitting a peak of 83,047 in France in 1900. As a promotional device, World’s Fairs and the potential awards that could be won there, remained a draw.

But over the next few decades, the number of exhibitors continued to dwindle. As the agricultural and industrial sectors of the economy shrunk in relation to services, many of the small-scale artisans and manufacturers that had comprised the bulk of the exhibitors were permanently phased out. In some sectors, corporations consolidated control. All the while, would-be exhibitors found other promotional outlets. Of course, there were also wars, recessions, geopolitical conflicts.

And when the exhibitors left, what was left? It was entertainment, amusement, spectacle, the midway rides, cultural villages, and outlandish shows. But in this respect, too, the fairs were doomed. A widespread consumer class, urbanization, and electrification meant that by 1906 in the United States, an “amusement park boom” had resulted in over 1,500 parks and a mania as every man “from almost all professions of life…without knowledge or particular ability in this line endeavored to build parks.” This had echoes abroad as well, with amusement parks “such as are to be found all over the United States” sprung up in urban centers and resorts all over Britain, reaching more than 30 by 1914. These ‘permanent fairs’ drew crowds by the millions, diluting the importance – and impact – of the world’s fair midway and amusement grounds.

This something for everyone, entire-universe-under-one-roof model was bound to decline. By the 1960s, the number – and character – of world’s fair exhibitors had changed drastically. At the San Antonio HemisFair of 1968, there were only 55 exhibitors, representing 25 countries, 21 corporations, and 2 US states. While the figure has increased in recent years – Dubai’s Expo 2020 featured 266 exhibitors, of which 190 were country pavilions. Corporate participation was limited to a handful of global brands like Emirates Air, Gatorade, L’Oreal, Mastercard, Canon, and Pepsi.

While world’s fairs no longer hold the central place they once did, their influence endures. The landmarks, cultural movements, technological advancements, and theme park rides they brought into existence, continue to shape the world. In the modern era, the spirit of world’s fairs lives on in specialized expos, trade shows, amusement parks, festivals, museums, and the myriad of individual attractions that continue to connect and inspire people around the world. And perhaps most importantly for readers of this blog, to imagine such an attraction once existed, all-encompassing and universal in theme, content, and appeal, is an inspiration for us all as we continue to conceptualize and plan these attractions that bring people together.

Bibliography:

The Pleasure Garden, from Vauxhall to Coney Island, Edited by Jonathan Conlin

World of Fairs, by Robert W. Rydell

History of the World’s Fair Being A Complete and Authentic Description of the Columbian Exposition From its Inception; E.B. Treat Publisher

The Crystal Palace Exhibition Illustrated Catalogue – London (1851)

Encyclopedia of World’s Fairs and Expositions, edited by John E. Findling and Kimberly D. Pelle